Staging and response assessment in lymphomas: the new Lugano classification

Introduction

With newer and more effective therapies for the treatment of lymphomas the need for universally accepted, standardized criteria for staging and response becomes even more critical. Such guidelines permit the reporting of uniform endpoints, facilitate comparisons amongst studies, help identify promising regimens, and facilitate evaluation and approval by regulatory agencies. This manuscript describes the evolution of staging and response criteria leading to the most recent Lugano classification (1).

Staging is used to define the anatomic distribution of the disease for purposes of prognosis and treatment planning. The first such system in lymphoma was a three stage classification published by Peters in 1950 (2) and was followed by the Rye classification of 1966 (3), and then the Ann Arbor classification of 1971 (4), which has remained the most widely used, until the present day. These were all designed for the initial evaluation of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) to assist radiation oncologists in planning their radiation delivery, as radiation was the only effective treatment at the time, and did not seem to be applicable to non-HL (NHL) at the time (5). Chemotherapy for HL was reserved for patients with advanced disease because of its toxicity and unknown efficacy. The Ann Arbor classification subdivided patients into four stages and further subdivided them based on the absence of (A) or presence of (B) disease-related symptoms: fevers >38 °C, drenching night sweats, unexplained fevers, and unintentional weight loss of >10% over the prior 6 months. The term “E” was used to designate proximal/contiguous extranodal disease. Imaging studies included intravenous pyelogram, ultrasound, liver-spleen scan, and the torture of the lymphangiogram. Staging laparotomy was performed for all but those with obviously advanced disease. As a result of that procedure, patients were given an additional designation based on the presence of disease involving the spleen, liver, bone, lung, and other sites. As technology and treatment improved, the Ann Arbor classification underwent modification. The Cotswold revision incorporated CT scans for staging (6). This improved imaging technique, along with the front-line use of effective, systemic chemotherapy rendered surgical exploration unnecessary (7,8). Bulky disease was designated “X”, and the term complete remission unconfirmed (CRu) was created for those patients with a residual mass posttreatment thought more likely to be fibrosis than actual tumor.

In 1999, an international working group made the first recommendations for response assessment for NHL (9), which were also adopted for HL. The terms complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), CRu, stable disease (SD), relapsed disease (RD) and progressive disease (PD) were codified. These guidelines became universally accepted by clinicians, the pharmaceutical industry, and regulatory agencies. However, as the recommendations were more widely used, it became apparent that a number of issues needed to be addressed. Some terms were unclear or misinterpreted (e.g., CRu), assessment was based largely on physical examination and standard laboratory tests, with imaging limited to chest X-ray, CT scans or MRI, gallium scan, and visual bone marrow evaluation. PET scans were invented in 1987 and first applied to lymphoma in 1990. The advantage of PET scans over CT was that PET was able to distinguish viable tumor from scar and fibrosis. PET could, therefore, eliminate the term CRu and clarify other issues in prior recommendations for both NHL and HL (10). PET, in conjunction with the availability of FDG-PET, immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry of the bone marrow justified the opportunity to update these recommendations with the international harmonization project recommendations (11). These guidelines published in 2007 incorporated PET scans for response became the international standard, and have been validated by other groups (12).

Following extensive experience with these criteria, and recognizing the progress made following their publication, particularly in imaging techniques, a workshop was held at the 11th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) in Lugano, Switzerland, June 2011. This workshop was attended by leading hematologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, and nuclear medicine physicians, representing major lymphoma clinical trials groups and cancer centers in North America, Europe, Japan, and Australasia. The aims were to develop universally accepted, unambiguous, improved staging and response criteria for HL and NHL, relevant for community physicians, investigator-led trials, cooperative group and registration trials that would permit improved lymphoma patient evaluation, enhance comparisons amongst studies, and simplify evaluation of new therapies. Two task forces were formed, one to identify clinical issues such as the current relevance of the Ann Arbor staging system, whether a simplification was possible, to evaluate the role of bone marrow biopsies and chest X-rays, improve organ assessment, redefine PD, to take into account novel consequences of new drugs, including tumor flare reactions; and standardize follow-up. The charge to the imaging task force was to update the relevance of existing imaging for staging and evaluating bulk and bone marrow involvement, to clarify the role of contrast enhanced CT scans (CeCT) versus low dose CT with PET-CT, discuss the role of interim PET-CT, and to evaluate the potential prognostic value of quantitative analyses using PET-CT and CT. A series of meetings and conference calls followed, and a subsequent workshop was held at the 12th ICML in Lugano, Switzerland in 2013. The result of those deliberations was the new Lugano classification (1).

Initial patient evaluation

The essential factor in patient management is making an accurate diagnosis. Fine needle aspiration of lymph nodes has a high likelihood of a false negative result, obtaining a nonrepresentative sample resulting in misdiagnosis, and not providing sufficient tissue for molecular and genetic studies, and, therefore, is strongly discouraged (13). An excisional biopsy is preferred, although a core biopsy may be acceptable when the former is not possible.

The next step is to perform a complete clinical evaluation which includes a careful history and physical examination, recording disease-related symptoms, measuring nodes and spleen size. Necessary laboratory tests include a complete blood count with differential, liver and renal function tests, uric acid, lactate dehydrogenase, and others as relevant to diagnosis (e.g., HIV), treatment (e.g., hepatitis B and C), or prognosis based on the currently used scoring systems (e.g., IPI, FLIPI, F-2, MIPI, IPS, etc.) (14-18).

Staging

A large number of studies have definitively demonstrated that PET-CT is the most sensitive of current imaging studies, and is highly specific, not only for response assessment, but for pretreatment determination of disease localization (19-23). Moreover, since it was accepted as the standard for restaging, it was reasonable to accept it for pretreatment staging (11). Thus, the new classification formally includes PET-CT as the standard imaging study for staging of FDG-avid lymphomas, which include all except for CLL/SLL, mycosis fungoides, and marginal zone (unless local radiation is considered as the sole modality of treatment) (24). Whereas, the goal of more sensitive staging techniques is that fewer patients undertreated or overtreated, a consequence is stage migration which can limit the ability to use historical comparisons. A contrast enhanced CT scan is also recommended if measuring nodes is important, or for radiotherapy planning.

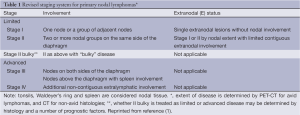

As noted above, the four stage Ann Arbor system was developed primarily to direct radiation therapy. Although in some situations, stages I and II NHL may be approached differently, they are often treated the same. Those with stages III and IV patients are almost always treated similarly. Therefore, there is rationale to reclassify patients as Limited or Advanced disease for treatment purposes, factoring in important risk factors, rather than simply by Ann Arbor stage. In HL, stages I and II may be approached differently, but III and IV are managed in a similar manner. Therefore I and II can be considered as limited disease, III and IV as advanced, and treatment based on various prognostic factors. Stage IIB can be approached as either limited or advanced, directed by disease setting and other risk factors (Table 1). In addition, the presence or absence of the disease-related symptoms of fevers, unexplained weight loss or drenching night sweats does not appear to correlate with outcome in any of the commonly used prognostic scores in NHL (e.g., IPI, FLIPI, F2, MIPI) and, thus, A and B do not need to be applied to NHL as they do not impact patient approach. In contrast A and B are still used to make some treatment decisions in early stage HL, and, therefore, are retained in that setting. Thus, the designation “X” for bulky is no longer used, but, instead, the greatest diameter of the largest mass should be recorded. The standard 10 cm or a third the transverse diameter of the chest was retained for HL, although as a single mass rather than a collection of smaller nodes with surrounding connective tissue. No consistent definition for bulky disease has been determined for NHL and, therefore, none was provided, with hopes that future studies would generate a data based definition, perhaps using tumor volume.

Full table

It is clear that certain components of staging have persisted more for historical than scientific reasons. For example, numerous studies have questioned the role of the bone marrow biopsy (BMBx) in staging of HL and diffuse large B-cell NHL (25-32). Recently, El-Galaly et al. (29) reported on 454 patients with newly diagnosed HL. In 18%, focal bone/bone marrow lesions were noted on PET-CT, but in only 8% by trephine biopsy. No patient with stage I-II by PET had a positive biopsy, and patients with a positive biopsy also had other evidence of advanced disease. All patients who were upstage by biopsy went from stage III-IV, with no alteration in treatment plan. Khan et al. (32) identified bone marrow involvement in 27% of 130 patients with DLBCL; 33 by PET and 14 by BM biopsy. PET identified all patients with a positive biopsy, and cases with a positive PET had an outcome comparable to other patients with stage IV disease without a positive bone marrow. Based on these data and others, the new recommendation is that a BMBx is no longer needed for the routine staging of patients with HL, and only for those with DLBCL with a negative PET for whom identification of occult discordant histology is clinically important (33). However, a bone marrow remains a standard test for staging other lymphomas.

A chest X-ray has also been a traditional test in staging, especially for HL. However, CT scans are the superior test (34), and there no longer appears to be a need for the radiograph in the routine assessment of patients with HL.

Response assessment

Restaging scans are generally performed 6-8 weeks following completion of treatment in the setting of regimens with a fixed number of cycles. However, a different time point may be needed for regimens where treatment is continuous or if maximum response is expected to be delayed. If a contrast enhanced CT was performed at baseline and showed no additional findings beyond those identified by PET, then a lower dose CT during restaging is adequate.

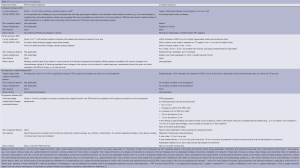

Although PET-CT was considered standard for staging in the 2007 guidelines (11), visual interpretation was used with the mediastinal blood pool as the comparator. Interobserver variability was a problem with this approach (35). The Deauville 5-point scale has been validated as a reliable means of interpreting scans in FDG-avid histologies (Table 1) and improves consistency of interpretation (36). Therefore, it will now be the standard for interpretation of response (Table 2). CT scans should still be used for the variably avid or negative histologies.

Full table

Patient follow-up

Once response has been assessed, further imaging studies should be performed judiciously and prompted by clinical indications. Surveillance scans are not justified strongly discouraged after that point, especially in HL and DLBCL. They are not cost-effective, and are associated with a high likelihood of false-positive results, leading to unnecessary imaging and biopsies. Several studies have shown that 70-80% of the time it is the patient or the physician who identifies recurrence, and additional scans lead to false positive results and are not cost-effective (37,38). A repeat study may be needed if the posttreatment scan was equivocal, or conservatively in patients with an indolent NHL and intraabdominal or retroperitoneal disease.

Conclusions

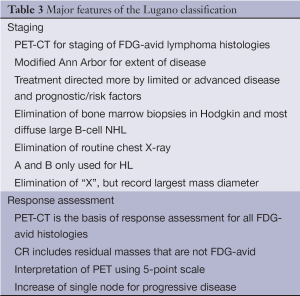

These new criteria have a number of features that distinguish them from the 2007 recommendations (11) (Table 3). FDG-PET-CT is the new standard for staging of all FDG-avid histologies. A modified Ann Arbor classification has been retained for extent of disease. However, patients should be treated more on the basis of risk factors. Vestiges of the past, including routine chest X-rays, the use of “X”, and bone marrow biopsies in HL and DLBCL are no longer indicated, and the designation A and B primarily for limited stage HL.

Nevertheless, a number of issues remain to be clarified. For example, the size of a nodal mass to be considered “bulky” disease with a clinically distinct approach and/or outcome remains to be elucidated. Whether tumor volume can be reliably incorporated into current clinical practice is unclear. Studies are evaluating more quantitative measures of assessing response to improve the predictability of PET, including the percent of reduction in the standard uptake to (SUV), the percent decrease in the size of the mass, alone or in combination (39-41). Until these questions and others are resolved, and newer, more powerful molecular and genetic prognostic factors are identified that impact treatment, these new staging and response criteria should serve to improve patient management.

Full table

Acknowledgements

The author expresses his most deep appreciation to his colleagues who were largely responsible for the original Lugano Classification manuscript: Richard I. Fisher, Sally F. Barrington, Emmanuele Zucca, Franco Cavalli, Lawrence B. Schwartz, and T. Andrew Lister.

Disclosure: The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3059-68. [PubMed]

- Peters MV. A study of survival in Hodgkin’s disease treated radiologically. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1950;62:299-311.

- Rosenberg SA. Report of the committee on the staging of Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Res 1966;26:1310. [PubMed]

- Rosenberg SA, Boiron M, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Report of the Committee on Hodgkin’s Disease Staging Procedures. Cancer Res 1971;31:1862-3. [PubMed]

- Rosenberg SA. Validity of the Ann Arbor staging classification for the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rep 1977;61:1023-7. [PubMed]

- Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin’s disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1630-6. [PubMed]

- DeVita VT Jr, Simon RM, Hubbard SM, et al. Curability of advanced Hodgkin’s disease with chemotherapy. Long-term follow-up of MOPP-treated patients at the National Cancer Institute. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:587-95. [PubMed]

- Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Santoro A. Alternating non-cross-resistant combination chemotherapy or MOPP in stage IV Hodgkin’s disease. A report of 8-year results. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:739-46. [PubMed]

- Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1244. [PubMed]

- Juweid ME, Wiseman GA, Vose JM, et al. Response assessment of aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by integrated International Workshop Criteria and fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4652-61. [PubMed]

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:579-86. [PubMed]

- Brepoels L, Stroobants S, De Wever W, et al. Aggressive and indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: response assessment by integrated international workshop criteria. Leuk Lymphoma 2007;48:1522-30. [PubMed]

- Hehn ST, Grogan TM, Miller TP. Utility of fine-needle aspiration as a diagnostic technique in lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3046-52. [PubMed]

- A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med 1993;329:987-94. [PubMed]

- Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 2004;104:1258-65. [PubMed]

- Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4555-62. [PubMed]

- Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2008;111:558-65. [PubMed]

- Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1506-14. [PubMed]

- Newman JS, Francis IR, Kaminski MS, et al. Imaging of lymphoma with PET with 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: correlation with CT. Radiology 1994;190:111-6. [PubMed]

- Thill R, Neuerburg J, Fabry U, et al. Comparison of findings with 18-FDG PET and CT in pretherapeutic staging of malignant lymphoma. Nuklearmedizin 1997;36:234-9. [PubMed]

- Buchmann I, Reinhardt M, Elsner K, et al. 2-(fluorine-18)fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in the detection and staging of malignant lymphoma. A bicenter trial. Cancer 2001;91:889-99. [PubMed]

- Schaefer NG, Hany TF, Taverna C, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease: coregistered FDG PET and CT at staging and restaging--do we need contrast-enhanced CT? Radiology 2004;232:823-9. [PubMed]

- Hutchings M, Loft A, Hansen M, et al. Position emission tomography with or without computed tomography in the primary staging of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica 2006;91:482-9. [PubMed]

- Weiler-Sagie M, Bushelev O, Epelbaum R, et al. (18)F-FDG avidity in lymphoma readdressed: a study of 766 patients. J Nucl Med 2010;51:25-30. [PubMed]

- Carr R, Barrington SF, Madan B, et al. Detection of lymphoma in bone marrow by whole-body positron emission tomography. Blood 1998;91:3340-6. [PubMed]

- Moog F, Bangerter M, Kotzerke J, et al. 18-F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography as a new approach to detect lymphomatous bone marrow. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:603-9. [PubMed]

- Moulin-Romsee G, Hindié E, Cuenca X, et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT bone/bone marrow findings in Hodgkin’s lymphoma may circumvent the use of bone marrow trephine biopsy at diagnosis staging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010;37:1095-105. [PubMed]

- Pakos EE, Fotopoulos AD, Ioannidis JP. 18F-FDG PET for evaluation of bone marrow infiltration in staging of lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Med 2005;46:958-63. [PubMed]

- El-Galaly TC, d’Amore F, Mylam KJ, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy has little or no therapeutic consequence for positron emission tomography/computed tomography-staged treatment-naive patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4508-14. [PubMed]

- Pelosi E, Penna D, Douroukas A, et al. Bone marrow disease detection with FDG-PET/CT and bone marrow biopsy during the staging of malignant lymphoma: results from a large multicentre study. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;55:469-75. [PubMed]

- Berthet L, Cochet A, Kanoun S, et al. In newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, determination of bone marrow involvement with 18F-FDG PET/CT provides better diagnostic performance and prognostic stratification than does biopsy. J Nucl Med 2013;54:1244-50. [PubMed]

- Khan AB, Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, et al. PET-CT staging of DLBCL accurately identifies and provides new insight into the clinical significance of bone marrow involvement. Blood 2013;122:61-7. [PubMed]

- Cheson BD. Hodgkin lymphoma: protecting the victims of our success. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4456-7. [PubMed]

- Bradley AJ, Carrington BM, Lawrance JA, et al. Assessment and significance of mediastinal bulk in Hodgkin’s disease: comparison between computed tomography and chest radiography. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2493-8. [PubMed]

- Horning SJ, Juweid ME, Schöder H, et al. Interim positron emission tomography scans in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an independent expert nuclear medicine evaluation of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group E3404 study. Blood 2010;115:775-7. [PubMed]

- Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, et al. Role of Imaging in the Staging and Response Assessment of Lymphoma: Consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3048-58. [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Yeap BY, Canellos GP, et al. Value of follow-up procedures in patients with large-cell lymphoma who achieve a complete remission. J Clin Oncol 1991;9:1196-203. [PubMed]

- Radford JA, Eardley A, Woodman C, et al. Follow up policy after treatment for Hodgkin’s disease: too many clinic visits and routine tests? A review of hospital records. BMJ 1997;314:343-6. [PubMed]

- Lin C, Itti E, Haioun C, et al. Early 18F-FDG PET for prediction of prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: SUV-based assessment versus visual analysis. J Nucl Med 2007;48:1626-32. [PubMed]

- Casasnovas RO, Saverot AL, Berriolo Riedinger A, et al. The 18F-FDG SUVmax reduction after two cycles of R-CHOP regimen predicts progression free survival of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2009;114:abstr 2931.

- Kostakoglu L, Schöder H, Johnson JL, et al. Interim [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in stage I-II non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma: would using combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography criteria better predict response than each test alone? Leuk Lymphoma 2012;53:2143-50. [PubMed]