Training of breast surgical oncologists

Introduction

The management of breast cancer has evolved dramatically since the Halstead radical mastectomy. Over the past several decades, there has been a paradigm shift from primarily surgical management to the incorporation of multimodality therapy and personalized care. Contemporary practice is defined by the understanding of tumor biology with increased emphasis on systemic and targeted therapy as well as minimally invasive and increasingly aesthetic oncologic techniques. This has shifted the role of the breast surgeon to embrace a multidisciplinary approach with an intimate understanding of the interaction of systemic therapy and local regional therapy. Additionally, distinguishing benign conditions and identification of high-risk patients who may benefit from risk reduction is an important factor. As a result, the surgical treatment of breast cancer and clinical decision-making have become increasing more complex and tailored validating sub-specialty training in breast surgical oncology.

Several decades ago, with increasing attention to breast cancer diagnosis and treatment the discipline of breast surgical oncology emerged. This specialization has been associated with more favorable oncologic and patient satisfaction outcomes (1-4). Furthermore, the need for specialized training is punctuated by the decreased comfort of surgical trainees in comprehensive breast cancer management and surgical techniques such as axillary dissection and modified radical mastectomy in general surgery residency (5).

Surgical societies and advocacy organizations recognized the growing need for formalized and focused training programs in breast surgical oncology within a multidisciplinary context. Leaders in the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBS), the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO), the American Society of Breast Disease (ASBD) and Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation developed a formalized fellowship in breast surgical oncology after the completion of general surgery residency (6). Over the years there has been tremendous growth in fellowship training from 26 programs with 31 positions in 2003 to 45 programs with 63 positions in 2015.

This review will examine breast surgical oncology training in the United States as well as components of a successful multidisciplinary fellowship program including curriculum, clinical research development and mentorship.

Multidisciplinary fellowship training in breast surgical oncology

A breast surgical oncologist is an oncologist who utilizes surgery as the primary mode of therapy (6). Critical to this role is the ability to identify which patients will benefit from local-regional therapy, synthesize the implications of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies in regards to the optimal operative approach and engage the patient in shared decision making in regards to their care. This model is the basis for current fellowship programs with the collective goal to train each fellow to be able to “apply an integrated interdisciplinary approach to the management of women with benign and malignant breast diseases in a compassionate manner” (7). Currently, programs are reviewed and approved with oversight from the SSO and ASBS. Candidates apply to approved programs through a centralized mechanism and participate in a traditional match process to determine their fellowship training program.

Breast surgical oncology fellowship structure

Over the course of 12 months, fellows dedicate the majority of their time to the surgery service gaining expertise in diagnosis of breast diseases, development of comprehensive treatment planning, counseling patients on treatment options, perioperative care and development of specialized operative techniques. This includes nipple areola sparing mastectomy, skin sparing mastectomy and oncoplastic techniques for breast conserving surgery as well as sentinel node dissection and targeted axillary dissection for appropriate initial node-positive patients for axillary staging following neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In addition to this intensive experience in surgical management fellows participate actively in rotations with breast medical oncology, radiation oncology, plastic surgery, diagnostic breast imaging, breast pathology, genetics, cancer screening and prevention and community outreach. This facilitates in-depth and comprehensive engagement in the entirety of the patient experience and treatment continuum. The knowledge gained from these multidisciplinary rotations is invaluable in providing a foundation by which trainees are able to integrate and incorporate broad oncologic decision making into specific operative plans to meet the needs of the patient and provide the optimal outcome.

Additionally, fellows are expected to actively participate in multidisciplinary tumor board and planning conferences. A formulized didactic curriculum with weekly lectures is critical. Inclusion of trainees in institutional multidisciplinary discussions regarding implementation of practice changing trials and development of future clinical trials have a tremendous impact in preparing fellows for clinical practice and leadership in breast surgical oncology.

In addition to an institutional didactic curriculum, the ASBS has developed the Breast Education Self-Assessment Program (BESAP), a web-based review module for self-assessment and learning in the multiple disciplines of breast oncology (8). BESAP is available to fellows nationwide and administered with a pre-test upon entering fellowship and post-test at the completion of training. During the course of the year fellows have access to this database of questions for self-assessment and continual learning as a supplement to their institutional training program.

National breast surgical oncology fellowship curriculum and training requirements

Recognizing the need to standardization of the fellowship experience across programs, the SSO in conjunction with the ASBS formalized a national curriculum with training requirements (9). This serves as a guideline for individual programs while allowing for flexibility based on the institutional needs and requirements. The curriculum is defined for benign breast disease, breast imaging, malignant breast disease, plastic and reconstructive surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical management/counseling for genetic syndromes, palliative intent surgery, community outreach and leadership, pathology and cancer rehabilitation.

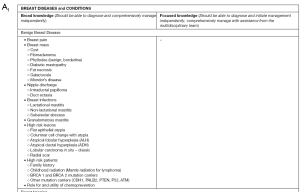

The curriculum is divided by diseases/conditions and procedures. Diseases and conditions are further classified into broad categories which every trainee should master following completion of the program and focused categories which the trainees should be able to recognize and diagnose but may also rely on participation with other providers. For example, in regards to breast imaging a broad knowledge and implementation of mammogram, ultrasound and MRI is required and focused knowledge of positron emission mammography and molecular breast imaging (Figure 1). Operations and procedures are classified by those which are essential and common, essential and uncommon and complex. This classification is based on the frequency of performance of this procedure by a breast surgeon (Figure 1). Additionally, minimum case numbers and training requirements are outlined including not only operations and procedures performed as in traditional surgical training but also non-operative exposure including evaluation and diagnosis of patients in medical oncology and radiation oncology and review of pathology and breast imaging (Figure 2). It is important to note that these are minimum requirements to establish and demonstrate proficiency and exposure in the multidisciplinary context and may likely be exceeded by many trainees during the course of their fellowship.

Engagement in clinical research within breast surgical oncology fellowship training

Clinical trials have shaped the evidence-based practice in breast oncology and surgical management. Knowledge of these trials and their applicability to an individual patient treatment is an important part of surgical oncology practice. Enrollment of eligible patients to clinical trials and leadership in clinical trial development should be encouraged. Additionally, fellows should participate actively in clinical research as a component of their training program. Not all training programs will have active clinical research trials available and therefore trainees at a minimum need to be involved with writing of relevant review articles in the field as well as basic retrospective clinical studies. Scholarly activity is essential and the intensity and curiosity of scientific inquiry addressing clinically relevant questions advancing our knowledge in the field is an important aspect to the maturation of a breast surgical oncologist.

Evaluation of breast surgical oncology training programs

Since their inception breast surgical oncology training programs have been further developed and refined to meet the needs of trainees and future patients. The SSO has stringent fellowship program requirements and together with the ASBS are involved with approval of training programs and each site has to be re-accredited each 5-years.

Sclafani and colleagues administered a survey to breast surgical oncology fellows from 2005 to 2009 regarding their fellowship training experience (10). The authors found among the 85 respondents, the majority reported that they were prepared for performing breast cancer surgery and understanding adjuvant therapy choices. The minority felt prepared to perform ultrasound (39.3%), ultrasound guided biopsy (28%) and stereotactic biopsy (19%). Thirty percent acquired additional skills to address this need in practice and the majority who did not perform these procedures indicated because image guided procedures were under the jurisdiction of radiology in their practice. In regards to research experience, 75% felt prepared to write an Institutional Review Board protocol, 89% to participate in clinical trials and 80% in cooperative groups. The majority participated in academic activity including poster or oral presentation, book chapter or peer-reviewed manuscript. The minority were participants in research cooperative groups including ACOSOG (13%), NSABP (10%), SWOG (10%) and CALGB (5%).

This survey highlighted a gap from training to practice in terms of image guided procedures. Also it suggested that the fellowship experience was variable by program with some fellows feeling unprepared for aspects of clinical practice. Subsequently, to address these training needs and provide for a standardized experience, the SSO organized and developed the Fellows Institute. This dedicated program is comprised of dedicated didactic sessions as well as hands on training in image-guided procedures complementing the fellows’ institutional training.

Simpson and Scheer utilized the Kirkpatrick evaluation model to evaluate the effectiveness of breast surgical oncology programs (11). This was achieved by application of relevant literature to the Kirkpatrick framework which evaluates “how trainees are reacting to the program, what they are learning from the program, how this is changing their behavior upon entry into practice, and finally the results the training programs are having on outcomes.” The authors concluded that the fellowship training programs in breast surgical oncology were effective; however, there was less direct published evidence of change in behavior and impact on patient outcomes defined as patient satisfaction/quality of life as well as oncologic outcomes. This data was limited as it utilized surrogates for fellowship training such as high volume centers and surgeons and membership in the SSO.

Further evaluation of the fellowship experience and needs are necessary to ensure training goals are achieved and to address areas for improvement in a dynamic and ever-changing learning environment.

The significance of mentorship in breast surgical oncology

Mentorship is a continuous thread connecting surgical leaders and trainees since the apprenticeship model of surgical training. Particularly in breast surgical oncology the importance of mentorship and development in the personal and professional growth of trainees is paramount. This is true as a trainee develops into an independent clinician, surgeon, researcher and educator. Similarly, as the field evolves so does the mentor-mentee relationship. Mentors not only provide themselves and their career as an example to mentees but also challenge, encourage, support and listen to them. Mentees should actively engage and nurture this relationship as well with enthusiasm, initiative, work ethic and support (12).

Furthermore, particularly in oncologic disciplines maintenance of a healthy balance of personal and professional spheres is important as clinical care may expose aspects of suffering, death and grieving. Cultivating this culture of resiliency, emotional intelligence and self-awareness is an important, often intangible, aspect of fellowship training. This will help to ensure a sustainable, worthwhile and satisfying career for our trainees and directly impact countless numbers of patients.

Future directions

This is a dynamic moment in surgical training in the United States. As general surgery residency trainees are increasingly pursuing specialty training and the intricacy of surgical disciplines develop, traditional surgical training paradigms are being reconsidered. Surgical oncology has recently become a specialty with board certification, an initiative supported and pioneered by the SSO, and accreditation of complex general surgical oncology (CGSO) training programs is presently under oversight by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) (13). Furthermore, there is increasing attention to competency based residency training as well as fast-track or early specialization into disciplines within general surgery.

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) is the “parent” organization of all medical boards, including the American Board of Surgery (ABS). The ABMS has just recently put forward a proposal through the ABS; this proposal is to allow the ABS to provide oversight of non-ACGME fellowship training programs. Specific details regarding which non-ACGME fellowships would be permitted to have an ABS certified fellowship are not yet available.

Finally, sub-specialization in oncoplastic breast surgery has gained favor as a designated specialty combining the oncologic and reconstructive aspects of breast surgical oncology in the United Kingdom. This provides a specialized focus within general surgery training which may be supplemented by a one year fellowship and further pursuit of a Master of Surgery degree in Oncoplastic Breast Surgery (14).

Conclusions

Breast surgical oncology is a specialty with increasing complexity in a multidisciplinary context. Similarly, fellowship training programs are growing in intensity and number with a standardized national curriculum developed by and oversight from the SSO and the ASBS. Core components of a successful program include instruction in surgical decision-making and techniques with attention to multidisciplinary practice in rotational structure and didactic curriculum and dedication to clinical research and mentorship. Fellowship programs continue to adapt to meet the needs of trainees and prepare them to provide high quality evidence-based patient care while continuing the research tradition and educational mission that drives the field of breast surgical oncology.

Acknowledgements

Funding: Supported in part by the P. H. and Fay Etta Robinson Distinguished Professorship in Research (to HM Kuerer) and U.S. National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support grant CA16672.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Quinn McGlothin TD. Breast surgery as a specialized practice. Am J Surg 2005;190:264-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skinner KA, Helsper JT, Deapen D, et al. Breast cancer: do specialists make a difference? Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:606-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillis CR, Hole DJ. Survival outcome of care by specialist surgeons in breast cancer: a study of 3786 patients in the west of Scotland. BMJ 1996;312:145-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waljee JF, Hawley S, Alderman AK, et al. Patient satisfaction with treatment of breast cancer: does surgeon specialization matter? J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3694-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson JP, Miller A, Edge SB. Breast education in general surgery residency. Am Surg 2012;78:42-5. [PubMed]

- Kuerer HK. Kuerer’s breast surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary training for breast surgical oncology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

- Society of Surgical Oncology. Interdisciplinary breast fellowship core educational objectives for SSO-approved training programs (2008). Available online: http://www.surgonc.org/training-fellows/fellows-education/breast-oncology/program-requirements

- American Society of Breast Surgeons. Breast education self-assessment program. Available online: https://www.breastsurgeons.org/educational/BESAP.php

- Society of Surgical Oncology. 2014 breast surgical oncology fellowship curriculum and minimum training requirements. Available online: http://www.surgonc.org/docs/default-source/pdf/2014_breast_fellowship_curriculum_training_requirements.pdf?sfvrsn=2

- Sclafani LM, Bleznak A, Kelly T, et al. Training a new generation of breast surgeons: are we succeeding? Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:1856-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simpson JS, Scheer AS. A Review of the Effectiveness of breast surgical oncology fellowship programs utilizing Kirkpatrick's evaluation model. J Cancer Educ 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singletary SE. Mentoring surgeons for the 21st century. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:848-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berman RS, Weigel RJ. Training and certification of the surgical oncologist. Chin Clin Oncol 2014;3:45. [PubMed]

- Down SK, Pereira JH, Leinster S, et al. Training the oncoplastic breast surgeon-current and future perspectives. Gland Surg 2013;2:126-7. [PubMed]