Anterolateral thigh flap harvested from paralyzed limbs in post-polio syndrome for tongue reconstruction—a case report and a review of the literature

Highlight box

Key findings

• Harvesting flaps from paralyzed limbs in post-polio syndrome is safe, which is in line with the sparse evidence from the literature.

What is known and what is new?

• Based on recent literature reports, anterolateral thigh, posterior tibial artery, and fibular flaps can be harvested from paralyzed lower limbs for reconstruction of head and neck defects, with no additional functional loss.

• In this paper, we added a description of the flap dissection techniques, postoperative complications and discussed the advantages and disadvantages of the flap.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This case study enhances the treatment experience with a special focus on pedicle and perforator characteristics as well as dissection techniques in paralyzed extremities, which are often considered as challenging conditions.

• In addition, emphasis should be placed on the prevention and treatment of systemic complications.

Introduction

Poliomyelitis accompanying head and neck cancer is rare. Donor-site selection for flap harvest is a very important issue in paralyzed patients, particularly in patients with post-polio syndrome (PPS). But the clinical experience on the usability of anterolateral thigh (ALT) flaps to repair soft tissue defects caused by tumor resection in patients with PPS is limited.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Poliomyelitis is an acute infectious disease caused by poliovirus in childhood, most commonly between 1 and 6 years of age, which affects the central nervous system by damaging the anterior horn cell of the spinal cord (1). Due to the success of poliovirus vaccination, poliomyelitis cases in China have steadily declined (2). About 15–80% (depending on data collection method and period) of nearly 20 million polio survivors worldwide experience limb weakness 15 to 30 years after an acute episode of poliomyelitis, which has been defined as PPS (3). PPS manifests mainly as flaccid paralysis in various muscle groups. The most commonly affected muscles are tibialis anterior, quadriceps, and tibialis posterior. The most common malformations are flexion-abduction contracture of the hip, flexion contracture of the knee and valgus foot (4).

Tongue cancer is the most common malignant disease of the oral cavity. The incidence of tongue carcinoma is increasing during recent years (5,6), and often shows an aggressive clinical course with a relatively poor prognosis (7). The 5-year relative survival rate is 63% (8).

The ALT flap is a free flap that is pedicled with the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery, which is composed of the ALT skin and a part of the vastus lateralis muscle. It has a long vascular pedicle and tissue versatility, which is suitable for matching various defects (9). According to a few related reports, it is proved that it is a reasonable method of functional preservation to harvest free flaps from paralyzed limbs of poliomyelitis patients to reconstruct tissue defects.

Objective

We report the case of a tongue carcinoma in a patient with paralyzed lower limbs secondary to poliomyelitis. Surgery is the first choice of treatment in such cases. Microvascular reconstruction has become a standard treatment to restore oral function after extensive tumor resection (10,11). The ALT flap, which can provide adequate tissue volume, is one of the most preferred options for reconstruction after total, subtotal, or hemi-glossectomy due to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (12-14). Consequently, an ALT flap was harvested from his left paralyzed limb for the reconstruction of an oral defect subsequent to tumor ablation. The clinical experience on the usability of ALT flaps to repair soft tissue defects caused by tumor resection in patients with PPS is limited. Therefore, our aim is to share our reconstruction experience, with a special focus on pedicle and perforator characteristics as well as dissection techniques in paralyzed extremities, which are often considered as challenging conditions. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cco-24-112/rc).

Case presentation

A 70-year-old wheelchair-bound man with a 4-month history of an ulcerated left tongue lesion presented to the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. Clinical examination revealed a 5 cm × 2 cm lesion on the left side of the tongue, extending to the lateral floor of the mouth and the right side of the tongue, with no lymphadenopathy. A spiral computed tomography of the head and neck and the thoracic region confirmed the lesion that presented without evidence of cervical or pulmonary disease. A preoperative biopsy revealed an oral SCC of the tongue. Thus, a SCC of the left tongue was diagnosed, with a TNM classification of cT4 cN0 cM0. The patient’s history revealed that he had suffered from acute poliomyelitis at the age of 2. He subsequently developed paraplegia and severe contractures of both lower extremities, and has been unable to walk since the age of 5. Several members of the patient’s family (including his parents and two daughters) have no similar history of poliomyelitis or oral cancer.

The patient was treated surgically and the surgical plan was subtotal glossectomy and bilateral neck dissection (levels I–IV), microvascular reconstruction with an ALT flap, as well as tracheotomy. The ALT flap to reconstruct the tongue was taken from the left paralyzed limb. A pencil probe for vascular Doppler was used preoperatively to demonstrate the presence and location of the perforators.

Flap dissection techniques

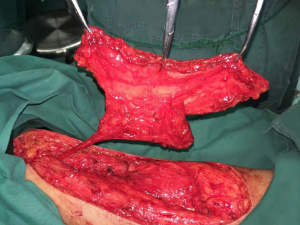

A line was drawn between the spina iliaca anterior superior and the superolateral corner of the patella, and a longitudinal skin incision was made approximately 2–3 cm medially of that line. The spina iliaca anterior superior could not be easily palpated because of the flexion contracture of the hip. In a healthy lower limb, a skin incision down to and through the thigh fascia exposes the rectus femoris muscle, but in a patient with poliomyelitis the vastus medialis muscle may be encountered due to significant muscle atrophy. The quadriceps muscle had a yellow, fat-like color and the intermuscular septum was not clearly identifiable (Figures 1,2).

In a paralysed lower limb, the vastus medialis muscle may be mistaken for the rectus femoris muscle due to muscle atrophy, it must be clearly identified. Once identified, the intermuscular septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis is incised. The rectus femoris muscle was pulled open to reveal the vascular pedicle of the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex. Subsequently, the femoral artery was inspected to ensure proper blood supply to the left lower limb, and intramuscular dissection of the musculocutaneous perforator was initiated from the distal to the proximal end. The distal end of the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery was ligated to obtain a myocutaneous ALT flap. The size of the skin island was approximately 18 cm × 6 cm and included two cutaneous perforators. The defect at the donor site was primary closed, and no healing deficits occurred in the later course (Figure 3).

The flap characteristics

Both skin and subcutaneous tissue were normal, similar to those of limbs unaffected by poliomyelitis. However, the rectus femoris muscle and vastus lateralis muscle showed atrophy with severe fat infiltration. Instead of the characteristic red color, the muscles had a yellow, fat-like color. Therefore, the intermuscular septum between rectus femoris muscle and vastus lateralis muscle was not clearly recognizable. Nevertheless, the caliber and length of the vascular pedicle and cutaneous perforators were similar to normal limbs.

Postoperative complications

Postoperatively, our patient suffered from acute respiratory insufficiency. Therefore, he was admitted to the intensive care unit with severe dyspnea, and a pneumonia was diagnosed. After immediate respiratory support, inspiratory muscle training and antibiotic treatment, he recovered and was transferred to the ward several days later.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Key findings

The harvesting of flaps from paralyzed limbs in patients with PPS has been demonstrated to be a safe and reliable procedure. The caliber and length of the vascular pedicle and cutaneous perforators exhibited similarity to those observed in normal limbs. Both donor and recipient sites demonstrated uneventful healing. However, it is imperative to note that postoperative respiratory complications and their management warrant close observation.

Comparison with similar research works

Based on recent literature reports, ALT flap, posterior tibial artery, and fibular flaps can be harvested from paralyzed lower limbs for reconstruction of head and neck defects without additional functional loss (15-21). It has been demonstrated that the posterior tibial artery flap has been used successfully; however, due to the sacrifice of the artery, concerns about long-term effects on the donor leg reduced its popularity (16). We found seven related articles in the English literature (Table 1), all of which show that the use of paralyzed, nonfunctional lower extremities as donor sites leads to no additional loss of function.

Table 1

| No. | Author | Age (years)/gender | Diagnosis | ALT flap | PTA flap | Fibula flap | Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Changchien et al. (15) | 53/M | Right lower gingival SCC (T4N0M0) | 1 | – | – | None |

| 51/M | Left buccal SCC (T4N0M0) | 1 | – | – | None | ||

| 2 | Chan et al. (17) | 53/M | Post-radiation sarcoma of left face | 1 | – | – | None |

| 3 | Valentini et al. (19) | 51/M | Right tongue SCC (T2N0M0) | 1 | – | – | None |

| 4 | Ulusal et al. (18) | 74/M | Left buccal SCC (T4N0M0) | 1 | – | – | None |

| 45/M | Right buccal SCC (T4N1M0) | – | 1 | – | None | ||

| 5 | Mardini et al. (16) | 39/M | Left buccal cancer | – | 1 | – | None |

| 45/M | Buccal cancer | – | 1 | – | None | ||

| 46/M | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma palate | – | 1 | – | None | ||

| 6 | Selva Sakthipalan et al. (20) | 69/M | Carcinoma of the mandible | – | – | 1 | None |

| 7 | Yuan et al. (21) | 55/M | Left tongue SCC (T3N3M0) | 1 | – | – | None |

ALT, anterolateral thigh; M, male; PTA, posterior tibial artery; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

The studies by Borg and Henriksson (22) and Grimby et al. (23) showed reduced capillarization in relatively large muscle fibers, and less marked perfusion in the affected limb, but no vascular occlusions or ischemic changes (24,25). Several literature reports could demonstrate that the vessels of PPS patients are normal in size and that the flap perfusion did not differ from the one of flaps harvested from a healthy limb (15-21). Previous studies have shown a downregulation of cutaneous inflammation with a decrease of vascular resistance as a result of the loss of sympathetic tone in paralysis due to spinal cord injury, theoretically leading to a change in the wound healing process (25,26). However, our patient had uneventful recovery, apart from the respiratory complication, for both the donor and recipient sites.

According to relevant literature, a PPS with respiratory compromise is observed in 25–28% of patients approximately 25–40 years after acute poliomyelitis (27). Patients with PPS often present with altered respiratory functions, aspiration risks, chronic pain syndromes and cold intolerance (27,28). Respiratory insufficiency, which is associated with hypoventilation, is often caused by respiratory muscle weakness, deformities of the chest wall such as scoliosis, and obstructive/central apnea (29). This should always be considered in cases of poliomyelitis affecting the respiratory muscles (30).

Strengths and limitations

Due to atrophy of muscles in PPS, perforator dissection was even easier and muscle bleeding was reduced as compared to healthy limbs. But the disadvantages of harvesting flaps from paralyzed limbs are that the amount of tissue may be limited. Therefore, it may not be suitable for cases requiring large amounts of tissue to fill the dead space, such as total tongue or skull base defects. However, it is suitable for large superficial defects. The positioning of patients with contracted legs may present a challenge.

Explanations of findings

ALT flap can be harvested from paralyzed lower limbs for reconstruction of head and neck defects without additional functional loss. A key consideration is the physical condition of patients with PPS, which is usually weak. Prolonged bedridden periods are associated with a high risk of complications. Attention must be paid to the patients’ respiratory functions, especially in the postoperative management. Accurate preoperative evaluation can often prevent postoperative complications. A simpler and much more widely available screening test is the vital capacity. In the event that the clinical features and the vital capacity are less than 1.0–1.5 liters, suggesting significant respiratory involvement, arterial blood gas analysis should be performed prior to surgery. The risk of hypoventilation can be mitigated by avoiding the use of muscle neuromuscular blocking agents during surgery and only discontinuing mechanical ventilatory support once the effects of the anesthetic agents have fully dissipated (30). Additionally, careful postoperative monitoring and non-invasive ventilation of patients with PPS is necessary (28), which should be accompanied by rehabilitation management with early physical therapy, including increased physical activity and muscle training (29).

Implications and actions needed

This case study enhances the treatment experience with a special focus on pedicle and perforator characteristics as well as dissection techniques in paralyzed extremities, which are often considered as challenging conditions.

At the same time, we should pay attention to the prevention and treatment of systemic complications.

Conclusions

Based on the current scientific evidence and on our experience, we believe that, in general, flap harvesting from the paralyzed limbs of patients with PPS is a safe and reliable approach for functional reconstruction after tumor resection. A preoperative pencil probe for vascular Doppler ultrasound is helpful and sufficient to determine the presence and location of perforators. Flap dissection should be carefully performed by a clear identification of relevant structures. During the postoperative management of patients, attention should be paid to respiratory complications such as pneumonia. An accurate preoperative evaluation can often prevent postoperative complications, and the initiation of early physiotherapy with respiratory training may be beneficial.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Selina Ackermann, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland. Furthermore, Bilal Msallem expresses his gratitude to the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital and the IAOMS Foundation for the opportunity granted to him through the IAOMS Foundation Fellowship 2019–2020.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cco-24-112/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cco-24-112/prf

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cco-24-112/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Groce NE, Banks LM, Stein MA. Surviving polio in a post-polio world. Soc Sci Med. 2014;107:171-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu WZ, Wen N, Zhang Y, et al. Poliomyelitis eradication in China: 1953-2012. J Infect Dis 2014;210:S268-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oluwasanmi OJ, Mckenzie DA, Adewole IO, et al. Postpolio Syndrome: A Review of Lived Experiences of Patients. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2019;9:129-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chu ECP, Lam KKW. Post-poliomyelitis syndrome. Int Med Case Rep J 2019;12:261-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel SC, Carpenter WR, Tyree S, et al. Increasing incidence of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in young white women, age 18 to 44 years. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1488-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng JH, Iyer NG, Tan MH, et al. Changing epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: A global study. Head Neck 2017;39:297-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bello IO, Soini Y, Salo T. Prognostic evaluation of oral tongue cancer: means, markers and perspectives (I). Oral Oncol 2010;46:630-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Dijk BA, Brands MT, Geurts SM, et al. Trends in oral cavity cancer incidence, mortality, survival and treatment in the Netherlands. Int J Cancer 2016;139:574-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pu JJ, Atia A, Yu P, et al. The Anterolateral Thigh Flap in Head and Neck Reconstruction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2024;36:451-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai YC, Li C, Zeng DF, et al. Comparative Analysis of Radial Forearm Free Flap and Anterolateral Thigh Flap in Tongue Reconstruction after Radical Resection of Tongue Cancer. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2019;81:252-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krakowczyk Ł, Maciejewski A, Szymczyk C, et al. The Use Of Anterolateral Thigh Flap (ALTF) For Functional Tongue Reconstruction With Postoperative Quality Of Live Evaluation. Pol Przegl Chir 2015;87:384-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen H, Zhou N, Huang X, et al. Comparison of morbidity after reconstruction of tongue defects with an anterolateral thigh cutaneous flap compared with a radial forearm free-flap: a meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;54:1095-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali RS, Bluebond-Langner R, Rodriguez ED, et al. The versatility of the anterolateral thigh flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:e395-407. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang PP, Meng L, Shen J, et al. Free radial forearm flap and anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of hemiglossectomy defects: A comparison of quality of life. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2018;46:2157-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Changchien CH, Chen WC, Su YM. Free anterolateral thigh flap harvesting from paralytic limbs in post-polio syndrome. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg 2016;3:50-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mardini S, Salgado CJ, Chen HC, et al. Posterior tibial artery flap in poliomyelitis patients with lower extremity paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:640-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan RC, Liu HL, Chan YW. Free-flap harvesting from paralytic limbs of poliomyelitis patients--a safe and feasible option. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2012;65:821-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulusal BG, Ulusal AE, Yeh CJ, et al. Free flaps harvested from paralytic lower extremities in patients with late polio sequel. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118:5e-7e; discussion 8e-9e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valentini V, Terenzi V, Cassoni A, et al. Anterolateral thigh flap harvested from paralytic lower extremity in a patient with late polio sequel. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012;40:e5-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selva Sakthipalan SR, Sridhar K, Pandian SK, et al. Mandible reconstruction using a vascularized fibula flap from a post-polio paralytic limb. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;50:1009-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan ZJ, Chen L, Cheng XX, et al. Preparation of anterolateral thigh flap from polio-affected lower limb: A safe surgical option that preserves patient’s motor function. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2025; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borg K, Henriksson J. Prior poliomyelitis-reduced capillary supply and metabolic enzyme content in hypertrophic slow-twitch (type I) muscle fibres. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991;54:236-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grimby G, Stålberg E, Sandberg A, et al. An 8-year longitudinal study of muscle strength, muscle fiber size, and dynamic electromyogram in individuals with late polio. Muscle Nerve 1998;21:1428-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grimby G, Hedberg M, Henning GB. Changes in muscle morphology, strength and enzymes in a 4-5-year follow-up of subjects with poliomyelitis sequelae. Scand J Rehabil Med 1994;26:121-30. [PubMed]

- Lo JK, Robinson LR. Postpolio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis. Part 1. pathogenesis, biomechanical considerations, diagnosis, and investigations. Muscle Nerve 2018;58:751-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarkowski E, Naver H, Wallin BG, et al. Lateralization of cutaneous inflammatory responses in patients with unilateral paresis after poliomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 1996;67:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Punsoni M, Lakis NS, Mellion M, et al. Post-Polio Syndrome Revisited. Neurol Int 2023;15:569-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lambert DA, Giannouli E, Schmidt BJ. Postpolio syndrome and anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2005;103:638-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez H, Olsson T, Borg K. Management of postpolio syndrome. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:634-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shneerson JM. Postoperative respiratory arrest in a post poliomyelitis patient. Anaesthesia 2003;58:608-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]