The role of perioperative immunotherapy with chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC)

Bladder cancer made up 573,000 new cases and 213,000 deaths worldwide in 2020 (1). Most bladder cancer histology is urothelial in nature. While majority would present with superficial bladder cancer, up to a quarter would have muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) which has a high propensity to progress or metastasize, hence treatment over the years has sought to improve treatment outcomes beyond radical cystectomy.

Durvalumab is a human IgG1k (immunoglobulin G1 kappa) antibody programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor with initial phase 1/2 results in previously treated locally advanced, metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) showing a confirmed objective response rate of 17% (2) that led to an initial United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approval although the drug manufacturer voluntarily withdrew durvalumab out of the market in 2021 after the phase III trial results of the DANUBE trial, which was a phase III randomized trial exploring durvalumab versus durvalumab and tremelimumab and chemotherapy showed disappointingly negative results [median overall survival (OS) was 15.1 months in the durvalumab/tremelimumab group compared to 12.1 months in the chemotherapy arm; hazard ratio (HR), 0.85; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.72–1.02; P=0.075] for the intention to treat analysis (3). However, moving up durvalumab in an earlier disease phase in combination with perioperative chemotherapy followed by adjuvant durvalumab in those who undergo radical surgery was evaluated in the NIAGARA trial and found to improve responses and outcomes.

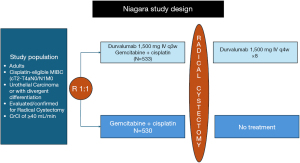

NIAGARA was a randomized 1:1 open-label randomized phase III trial that included 1,066 patients who were eligible for cisplatin chemotherapy and medically fit to undergo radical cystectomy, and evaluated the role of perioperative durvalumab with cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by post-operative durvalumab compared with perioperative chemotherapy alone with a dual primary endpoint of event-free survival (EFS) and pathological complete response (pCR) which were both assessed as blinded independent central pathological review (Figure 1) (4). The durvalumab group received neoadjuvant durvalumab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin every 3 weeks for four cycles, followed by radical cystectomy and adjuvant durvalumab every 4 weeks for eight cycles. The control group received neoadjuvant gemcitabine-cisplatin followed by radical cystectomy alone without adjuvant therapy. The trial enrolled patients who were considered cisplatin-eligible, though the definition of cisplatin eligibility was broader. It included a limited enrollment (capped at 20%) of patients with creatinine clearance of 40 to 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 of body surface area. Eligible tumor characteristics included non-metastatic disease with a T stage of T2 (capped to 40%), T3, T4, N0 or N1 and M0 disease according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging 8th edition. In addition, these were all considered to be stratification factors upon randomization. About 83% to 87% of patients had pure urothelial cancer, with a minority with variants, with squamous differentiation, glandular differentiation or other subtypes.

The initial analysis of pCR showed significant statistical difference between the two groups (33.8% for the durvalumab group versus 25.8% for the chemotherapy alone group, risk ratio, 1.30; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.56; P=0.004). However, pathological re-analysis performed showed there was a slight numerical difference in the pCR rates (37.3% for durvalumab versus 27.5% in the comparator chemotherapy alone group), though risk ratio remains similar (1.34, 95% CI: 1.13–1.60). The EFS at 24 months was found to be 67.8% (95% CI: 63.6% to 71.7%) in the durvalumab group and 59.8% (95% CI: 55.4% to 64.0%) in the comparison group (HR, 0.68; 95% CI: 0.56 to 0.82; P<0.001 by stratified log-rank test). Additionally, the OS at 24 months was found to be 82.2% (95% CI: 78.7% to 85.2%) in the durvalumab group and 75.2% (95% CI: 71.3% to 78.8%) in the comparison group (HR, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.59 to 0.93; P=0.01 by stratified log-rank test). In terms of treatment related adverse events, the durvalumab and control group had comparable results with 40.6% and 40.9%, respectively.

This study took a novel approach by integrating immunotherapy into the perioperative setting, building on ongoing efforts to advance immunotherapy in the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. The results demonstrated significant improvements in EFS and OS with perioperative use of durvalumab plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) compared to NAC alone. Another strength of the study was the stratification of patients based on PD-L1 expression, highlighting the potential for biomarker-driven therapy in bladder cancer. Lastly, the addition of immunotherapy did not lead to an increase in grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events compared to NAC alone.

The results of the NIAGARA trial herald a definite advance towards improvement in the outcomes of MIBC patients. There were several unique characteristics of the trial including enrollment of patients who were considered cisplatin-eligible but pushed the boundaries of creatinine clearance from 40 to <60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 of body surface area though this was added as a stratification criterion as well. In addition, patients could have received split-dose cisplatin, which was an added criterion of giving cisplatin in the community where most trials would not have allowed for such treatment. This population made up 19% of the patient population and given consistent findings of improved response with cisplatin compared to carboplatin, this undoubtedly increased the patient population who would otherwise not have been good candidates for cisplatin-based chemotherapy, an essential partner of durvalumab in this patient population.

The results of the NIAGARA trial mark the first trial that showed benefit in this perioperative setting population though it brings about several important clinical questions. Previous smaller phase II trials on immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) with the use of pembrolizumab (PURE-01) (5) showed an EFS at 2 years of 74.4% and OS at 83.8% in the intention-to-treat population whereas the use of atezolizumab in the cisplatin-ineligible neoadjuvant patient population (ABACUS trial) (6) showed a pCR rate of 31%, 2-year disease-free survival (DFS) and OS rates of 68% and 77%, respectively. In addition, the 2-year DFS in those who achieved a pCR was 85%. The NIAGARA trial also did not include an ICI-only arm as a perioperative approach, hence unclear if it would have been comparable or better than one with the chemotherapy combination. It should be remembered that all patients had to be cystectomy-eligible, although about 6% to 7% of patients ended up declining cystectomy. Therefore, it remains unknown if trimodality therapy or bladder preservation strategies would be an appropriate substitute for cystectomy in these perioperative treatment approaches.

In addition, while the use of this regimen combines chemotherapy with ICI, use of non-chemotherapy containing regimens such as antibody drug conjugates (ADC) abound. The results of the perioperative Keynote 905 with the use of enfortumab vedotin (EV) in combination with pembrolizumab, are also eagerly awaited. There are other trials in this perioperative state that are worthy of mention (see Table 1). This includes the EV-304 trial that utilizes EV + pembrolizumab (EV+P) (7), EV-303/Keynote-905 trial that utilizes EV+P in the cisplatin-ineligible population (8), VOLGA trial for the cisplatin-ineligible patient population (9), ENERGIZE trial for cisplatin-eligible patients comparing gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy with nivolumab and an oral selective IDO inhibitor linrodostat mesylate (BMS-986205) (10), Keynote-866 which utilized ICI + gemcitabine/cisplatin chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone + placebo with surgery (11). A key area of interest is the need for further adjuvant durvalumab in those who achieved good pCR and whether it is necessary. This may be where additional biomarker use such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) might be helpful to prognosticate survival and identify patients who are highest risk for recurrence and intervention, and incorporated in several adjuvant trials including the ALLIANCE trial called MODERN (clinicaltrials.gov NCT05987241), which is a phase II/III trial with the primary objective of seeking clearance of ctDNA as well as OS and DFS in those who undergo adjuvant nivolumab depending on clearance or presence of ctDNA. Lastly, this trial also did not include upper tract urothelial cancer patients, which some neoadjuvant trials do include and hence, extrapolation to the upper tract urothelial cancer patients may not be appropriate.

Table 1

| Trial name | Study population | Eligibility | Experimental arms | Control arms | Primary endpoint | Clinicaltrials.gov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIAGARA | 1:1 cisplatin-eligible | T2-T4a, N0, N1, M0; T2 capped at 40% | Durvalumab 1,500 mg with gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 D1 & D8 + cisplatin 70 mg/m2 D1 q 3 wks × 4 with durvalumab 1,500 mg q4 wks × 8 cycles after RC | Gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 D1 & D8 + cisplatin 70 mg/m2 D1 q 3 wks × 4 cycles followed by RC | Dual primary end points: pCR and EFS by BICR | NCT03732677 |

| EV-303/Keynote 905 | 1:1:1 cisplatin-ineligible | T2-T4aN0M0 or T1-T4aN1M0) with predominant (≥50%) urothelial histology | Neoadjuvant Px 3 cycles followed by RC + PLND and 14 cycles of adjuvant P (arm A) or 3 cycles of neoadjuvant EV and P (arm C) followed by RC + PLND and adjuvant EV + P × 6 cycles and 8 cycles of adjuvant P | RC + PLND alone (arm B) | EFS between arm B vs. arm C | NCT03924895 |

| KEYNOTE-B15/EV-304 | 1:1 cisplatin-eligible | T2-T4aN0M0 or T1-T4aN1M0) with predominant (≥50%) urothelial histology, have nonmetastatic disease (≥ N2 disease and/or M1 excluded) | 4 cycles of neoadjuvant EV + pembrolizumab followed by 5 cycles of adjuvant EV + 13 cycles of adjuvant pembrolizumab after RC + PLND or 4 cycles of neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by observation after RC + PLND | 4 cycles of neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by observation after RC + PLND | pCR and EFS by BICR | NCT04700124 |

| VOLGA | 1:1:1 cisplatin-ineligible | T2-4aN0-N1M0 | (Arm 1) D (1,500 mg day 1) + T (75 mg day 1) + EV (1.25 mg/kg days 1 & 8); (Arm 2) D (1,500 mg day 1) + EV (1.25 mg/kg days 1 & 8) | RC + PLND only | dual primary endpoints are pCR and EFS | NCT04960709 |

| ENERGIZE | 1:1:1 cisplatin-eligible | T2-T4aN0M0 | Arm B: gemcitabine/cisplatin + nivolumab or nivolumab and BMS-986205 followed by RC + PLND with adjuvant nivolumab +/− BMS-986205 | Arm A: gemcitabine/cisplatin chemotherapy | OS | NCT03661320 |

| Keynote 866 | 1:1 cisplatin-eligible | T2-T4aN0M0 | 4 cycles of neoadjuvant pembro + CT followed by 13 cycles of adjuvant pembro after RC + PLND | RC + PLND with neoadjuvant and adjuvant placebo | Dual primary endpoints pCR and EFS | NCT03924856 |

BICR, blinded independent central review; CT, computed tomography; EFS, event-free survival; EV, enfortumab vedotin; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; MIBC, muscle-invasive bladder cancer; OS, overall survival; pCR, pathological complete response; P, pembrolizumab; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; RC, radical cystectomy.

In summary, the role of perioperative ICI continues to evolve in MIBC as it has in the mUC disease state. As of March 28, 2025, this regimen has garnered regulatory approval by the US FDA, it is foreseen to change the landscape of MIBC treatment. However, questions remain including the need to offer adjuvant ICI to those who have achieved good pathological response or conversely, for those who do not, is there a role to switch to a different drug regimen or different ICI. While the positive trial that is reported here is limited to the cisplatin-eligible population, efforts to further evaluate utilizing the non-chemotherapy regimens with EV and pembrolizumab will be anticipated to further define the MIBC treatment algorithm and results are eagerly awaited.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Chinese Clinical Oncology. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cco-25-8/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cco-25-8/coif). J.B.A-C. serves on the Speakers’ Bureau of BMS, EMD Serono, and Astellas/Seagen; J.B.A-C. has served on the Advisory Board for Pfizer/Myovant, Astellas and Bayer, Merck, Pfizer, Astellas/Seagen, and AstraZeneca. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Jubber I, Ong S, Bukavina L, et al. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. Eur Urol 2023;84:176-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powles T, O'Donnell PH, Massard C, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Durvalumab in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Updated Results From a Phase 1/2 Open-label Study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:e172411. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Castellano D, et al. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1574-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powles T, Catto JWF, Galsky MD, et al. Perioperative Durvalumab with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Operable Bladder Cancer. N Engl J Med 2024;391:1773-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basile G, Bandini M, Gibb EA, et al. Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and Radical Cystectomy in Patients with Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Bladder Cancer: 3-Year Median Follow-Up Update of PURE-01 Trial. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:5107-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szabados B, Kockx M, Assaf ZJ, et al. Final Results of Neoadjuvant Atezolizumab in Cisplatin-ineligible Patients with Muscle-invasive Urothelial Cancer of the Bladder. Eur Urol 2022;82:212-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoimes CJ, Bedke J, Loriot Y, et al. KEYNOTE-B15/EV-304: Randomized phase 3 study of perioperative enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in cisplatin-eligible patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). J Clin Oncol 2021;39:TPS4587. [Crossref]

- Galsky MD, Necchi A, Shore ND, et al. KEYNOTE-905/EV-303: Perioperative pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus enfortumab vedotin (EV) and cystectomy compared to cystectomy alone in cisplatin-ineligible patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). J Clin Oncol 2021;39:TPS507. [Crossref]

- Powles T, Drakaki A, Teoh JYC, et al. A phase 3, randomized, open-label, multicenter, global study of the efficacy and safety of durvalumab (D) + tremelimumab (T) + enfortumab vedotin (EV) or D + EV for neoadjuvant treatment in cisplatin-ineligible muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (VOLGA). J Clin Oncol 2022;40:TPS579. [Crossref]

- Sonpavde G, Necchi A, Gupta S, et al. ENERGIZE: a Phase III study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone or with nivolumab with/without linrodostat mesylate for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Future Oncol 2020;16:4359-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siefker-Radtke AO, Steinberg G, Bedke J, et al. KEYNOTE-866: Phase III study of perioperative pembrolizumab (pembro) or placebo (pbo) in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cisplatin (cis)-eligible patients (pts) with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Ann Oncol 2019;30:v401. [Crossref]