The diagnosis and management of cystic lesions of the pancreas

IntroductionOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Cystic lesions of the pancreas are radiographic findings that have a very broad histologic differential. This differential spans the spectrum from benign to cancerous, and includes non-neoplastic pseudocysts, benign neoplastic cysts, pre-malignant cysts, and cystic lesions with invasive carcinoma (1). Because of the increased use of high-quality cross-sectional imaging, an increasing number of patients are being identified with small asymptomatic cysts, and the management of these patients has become very controversial (2,3). The controversy surrounding treatment recommendations centers on the inability to determine an exact histopathologic diagnosis without resection, and the recognition that many of these lesions will be precancerous intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN). Because of this diagnostic uncertainty and the potential for malignancy to develop in some patients, many authors have previously recommended routine resection of all pancreatic cysts (4,5). It should be emphasized, however, that the ability to determine the histologic diagnosis of pancreatic cysts without resection continues to improve, and our current imaging and endoscopic techniques may often differentiate benign cysts from pre-cancerous cysts of the pancreas. In addition, even within the precancerous mucinous sub-group, our ability to detect high-risk lesions is improving.

Because of improvements in diagnosis, we have recommended a more selective approach to resection (6-8). We have found that with current imaging techniques, and with the improved understanding of the various histologic entities, a group of patients can be identified who have an extremely low risk of malignancy. Within this group of patients, we routinely recommend non-operative management (radiographic follow-up). These patients typically have small (<3 cm), incidentally discovered cysts of the pancreas that do not have a solid component or other concerning clinical or radiographic features of malignancy (such as main pancreatic duct dilation). In addition, when patients can be identified who have benign lesions such as serous cystadenoma (SCA), recommendations regarding long-term surveillance can focus on issues surrounding local growth and progression, rather than the development of carcinoma. This selective approach to resection avoids the risks of operation in patients with benign lesions, but with current limitations in non-resectional diagnosis, cannot guarantee that a malignancy is not mistakenly being observed. Operative mortality rates following pancreatectomy range between 2% and 15% and significant postoperative complications occur in approximately 45% of patients. Our data suggest that with current imaging and endoscopic techniques a group of patients with pancreatic cysts can be identified with a malignancy rate of <3% (8). In this group of patients, the risk of death from pancreatectomy exceeds the risk of the lesion being malignant, and radiographic surveillance should be recommended.

When the histopathology of a given cyst can be determined non-operatively, the treatment recommendations may be less challenging. In these instances, recommendations can be made based on the known natural history of the specific histologic entity. For instance, when diagnostic evaluation identifies a patient with a SCA radiographic surveillance should be the routine recommendation. Resection for SCA should be reserved for the symptomatic patient, or in a healthy patient in whom significant growth has been observed. Presently, the most challenging group of patients are those with IPMN. Controversy over the management of these patients exists because of the difficulty in identifying those with high-grade dysplasia or early invasive carcinoma, the known predilection for whole gland involvement, and the lack of understanding as to the frequency and timing of malignant progression. In this chapter we will outline the histopathologic and biologic differences between the three most common cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, SCA, mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), and IPMN. Recommendations regarding the management of these lesions will also be considered.

SCAOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

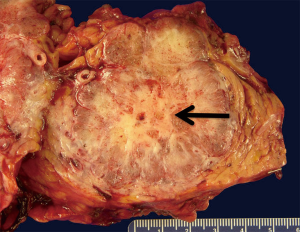

SCA are benign neoplasms composed of simple cuboidal epithelium that exhibits benign cytologic features (small round uniform nuclei, well defined cellular borders, glycogen rich cytoplasm). Grossly, the cystic tumors are well circumscribed, multinodular and may present with a wide range of sizes (Figure 1). The histologic architecture forms multiple small cysts or loculi yielding the microcystic pattern which may be evident on cross-sectional imaging. A macrocystic (oligocystic) variant has also been described in which the cyst is composed of larger and fewer loculi (9).

Clinically, the mean age at diagnosis of SCA is 61–65 years. Most reports have found a female to male predilection (7:3). These cysts are often detected incidentally by ultrasound or cross-sectional imaging performed for other reasons. SCA are typically asymptomatic until they reach a sufficient size to cause symptoms, which may include biliary obstruction or gastric outlet obstruction. Radiographic characteristics include a fine honeycomb pattern on computed tomography (CT) which is indicative of their microcystic morphology, and a central calcified scar. On endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the microcystic pattern may also be recognized, and when present, may obviate the need for fine-needle aspiration (FNA). The macrocystic variant can appear similar to mucinous tumors on both CT and EUS. Cyst fluid analysis of serous neoplasms usually reveals a fluid of low viscosity that is low in amylase as well as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (10). Cytology may often be paucicellular and thus non-diagnostic, but when neoplastic cells are present they may be identified as rich in glycogen, and cuboidal in shape.

SCA are almost invariably benign and resection should be reserved for symptomatic lesions, or occasionally for a very large or growing lesion in a young patient. Malignant degeneration has been described, but there remain fewer than 20 case reports of metastatic SCA in the world’s literature (11). Because the risk of malignancy is certainly lower than the risk of mortality from resection, we generally advocate a nonoperative approach for asymptomatic patients. Some authors advocate resection in asymptomatic serous cystic neoplasm when they reach 4 cm in diameter. These recommendations have been based on some studies which have suggested as faster growth rate in lesions once this diameter is attained (12). We have not found an increased growth rate in patients with larger lesions, and therefore typically do not use size alone as a criterion for resection.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)Other Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

SPN are rare tumors of the pancreas that exhibits solid growth with cystic degeneration. This characteristic will often result in the findings of both solid and cystic areas on imaging. The cavities that form from this cystic degeneration do not contain an epithelial lining and thus these should not be considered “true” cysts. These tumors are most frequently identified in young females (mean age, 25 years; male:female ratio, 1:9), and generally express progesterone and estrogen receptors. Because of these features, estrogen and progesterone have been indicated in their pathogenesis (13). These are slow growing tumors with metastatic potential and thus SPN should generally undergo resection. Even when these tumors metastasize, their biology is typically one of slow progression. Because of this, surgical resection may be considered in selected patients who have metastatic disease confined to the liver.

MCNOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

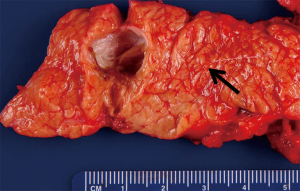

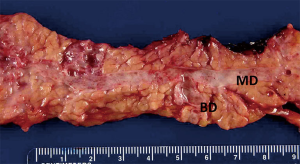

MCN of the pancreas are often large unilocular cysts characterized by a mucin producing epithelium and ovarian like stroma (Figure 2). Because of this latter feature, these lesions are almost exclusively found in women. These lesions tend to occur in the body/tail of the pancreas, and by definition do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system (Figure 3) (14). The epithelium of these cysts can demonstrate a wide range of architecture ranging from a uniform simple epithelium, to prominent papillary folds that can form a cribriform pattern. These prominent folds may manifest as intraluminal polypoid masses or septations which can be detected on cross-sectional imaging or EUS. Furthermore, the epithelium may display areas of normal epithelium abruptly separated from other areas of dysplastic to frankly carcinomatous epithelium. For this reason, biopsy of these lesions should not be used to rule out the presence of malignancy as the entire cyst should be examined to make this determination.

Clinically, MCN occur almost exclusively in females with a mean age at diagnosis of 48 years and female to male ratio of at least 10:1 (15,16). Some reports have suggested that these lesions occur only in women, and if ovarian-like stroma is a pre-requisite then the occurrence in males is extraordinarily uncommon. The majority of patients will have these lesions identified incidentally, as symptoms will occur only when these lesions become quite large. Diagnostically, these cysts yield a unilocular pattern on CT and may have a similar appearance to macrocystic serous cystic neoplasms, or branch duct IPMN. MCN should be considered likely when the patient is a young female with a single unilocular cyst in the tail of the pancreas. Occasionally, peripheral “eggshell” calcification may be seen (<20%) and this finding is almost pathognomonic for MCN (17). Cyst fluid analysis of these lesions generally reveals a viscous fluid that is low in amylase, and high in CEA. Cytology may range from acellular to mucin containing epithelial cells with a low-grade to malignant morphology.

MCN may undergo a transformation from benign to malignant that is thought to occur in a stepwise fashion (18). Because a negative biopsy does not rule out an early malignancy, there is no way to definitively rule out a malignancy other than by removing the cyst. Because these lesions are typically discovered in young patients, are generally in the pancreatic tail, and because surgical resection results in a complete cure of the lesion, many centers will recommend surgical resection for all patients with MCN. Unlike patients with resected IPMN, patients who have undergone resection for MCN have not been shown to have any increased risk of new lesions or cancer in their pancreatic remnant. Complete surgical resection produces an almost 100% cure rate for all lesions including carcinoma in situ, whereas, the survival for invasive cancers has been reported to be 30–40% (19).

Several large series of resected MCN, including one from our own institution, have reported no incidence of malignancy when these lesions are without a solid component and small (<3 cm) in size (7,20). In a review by Goh et al. (20) of 344 patients with resected MCN of the pancreas the mean tumor size of malignant cysts was 10.2 cm and no patient with a lesion <3 cm had malignancy. Because of this, our current approach for incidentally discovered MCN without a solid component is selective resection. In a young patient the long-term risk of malignant progression may outweigh the risks of pancreatectomy and resection should be considered. In the very elderly however this risk: benefit ratio may not warrant operation.

IPMNOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

IPMN was first described in Japan in 1982 as a “mucin producing” cancer of the pancreas. Since that time, it has undergone several changes in nomenclature from “mucinous ductal ectasia” to its current name given in the mid 1990s (21). IPMN is defined pathologically as a neoplastic proliferation of mucin producing cells that can involve a focal segment of the ductal system, multiple foci or even the entire ductal system. The epithelium tends to form papillary structures that have been characterized primarily as intestinal-like (morphologically similar to colonic villous adenomas) or pancreaticobiliary like (similar to papillary tumors of the biliary tract) (22). As the classification of these lesions has become more refined, additional histopathologic sub-types such as gastric and oncocytic have been described. In many instances, there will be a combination of these histologic sub-types in any given cyst. IPMN may involve primarily the main duct or a branch duct with the latter tending to show less aggressive pathologic features (Figure 4) (23). Because of this, radiographic involvement of the main duct (main duct dilation on imaging), or branch ducts (cystic disease without main duct dilation), has become the primary factor determining surgical treatment recommendations.

Histopathologically, dysplasia in IPMN has been characterized as low-grade, intermediate grade, high grade, or invasive. Invasive lesions should be further classified as to whether they are colloid (mucinous lakes with scanty malignant epithelium) or tubular (common ductal type). This distinction is important as the outcome for patients with invasive colloid carcinoma has been shown to be much more favorable than patients with tubular sub-type (24). In a study from our institution, estimated 5-year survival in patients with resected colloid carcinoma was 87%, compared to an estimated 5-year survival of 57% in patients with resected invasive tubular IPMN. The timing and frequency of IPMN from low-grade dysplasia to invasive cancer is unknown. A study from Johns Hopkins noted that the average age of patients with main duct IPMN and invasive tumors was approximately 6 years older than those with low-grade lesions, and therefore some have concluded IPMN follow the typical adenoma to carcinoma sequence and that this sequence takes somewhere between 5 to 10 years (25).

In distinction from MCN, IPMN display no gender predilection and tend to be identified later in life (typically in 7th to 8th decade of life). When symptomatic, they most commonly cause abdominal pain, but have also presented with symptoms of pancreatitis, jaundice or weight loss. On imaging, IPMN can be seen as cystic structures (branch duct IPMN) with or without an associated solid component. The diagnosis of IPMN should be further considered when there is evidence of communication with the main duct (main ductal type). Cyst fluid assessment from patient with IPMN is typically high in viscosity and CEA, and may also show an elevated amylase.

The management recommendations regarding operative resection of IPMN should include the risks of the operation, the risks of malignancy of the specific lesion, and the future risk of developing malignancy within the remnant gland if partial pancreatectomy is pursued. When cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic studies are characteristic of main-duct IPMN (MD-IPMN) then operative resection is typically recommended as the risk of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease is as high as 40–50%. The larger controversy regarding management of MD-IPMN is over the extent of pancreatic resection. Because many consider IPMN to represent a defect within the entire ductal system there is concern that removal of just part of the pancreas is inadequate. Patients who undergo less than total pancreatectomy for non-invasive IPMN have been found to have the potential to develop recurrent disease in the pancreatic remnant. A recent study from our center of 79 patients who underwent resection for non-invasive IPMN identified invasive remnant gland recurrence in 8% of patients after a median follow-up of 36 months (26). This is certainly a concern, however, given the relatively low rate of remnant recurrence we do not at this time recommend total pancreatectomy for all patients with MD-IPMN. When there is diffuse gland involvement radiographically, and when there is no overt radiographic evidence of invasive disease, total pancreatectomy may be warranted in selected patients with MD-IPMN. When there is evidence of an invasive carcinoma total pancreatectomy should be avoided as disease outcome will be dictated by the invasive lesion. When less than total pancreatectomy is performed postoperative surveillance is necessary in all patients.

This question of how much pancreas to resect in IPMN is complicated by the fact that the pathology can be multifocal, or even diffuse, making curative regional pancreatectomy a major challenge. For this reason, frozen section analysis of the margin has been argued by some to be a critical component to the surgery. Salvia et al. reported that in 29 of 140 cases the results of the frozen transection margin altered the surgical plan (27). However, the value of performing frozen section of the margin is a controversial subject. Many have argued that the status of the margin has no association with gland recurrence; however, many of these reports did not distinguish non-invasive from invasive IPMN (28). Recurrences following resection of an invasive IPMN are for the most part distant, making margin status and pancreatic remnant recurrence less important. Alternatively, in non-invasive IPMN a positive margin, particularly for high-grade dysplasia, may increase the likelihood of pancreatic remnant recurrence and we believe that further resection should be considered in this circumstance.

Because of the low-risk of malignancy in branch-duct IPMN (BD-IPMN), and because of the risks associated with pancreatectomy, our current approach to resection of the incidentally discovered BD-IPMN is selective. Resection is generally performed in the setting of symptoms, or concerning radiographic features (solid component, increasing size). Our typical follow-up schedule for patients undergoing non-operative management consists of high-quality cross-sectional imaging every 6 months for 2 years, and then annually thereafter. Resection is generally performed when there is any radiographic change in the lesion such as significant growth, the development of a solid component, or mural nodularity.

Regardless of whether treatment recommendations are for initial resection or radiographic surveillance, we believe that these patients should receive long-term radiographic follow-up. In a recent study from our group, 3,024 patients were analyzed who had been treated for a cystic lesion of the pancreas (29). Within this group of patients, 2,472 (82%) underwent initial radiographic surveillance, and 596 of these patients had been followed for more than 5 years. Regardless of the duration of follow-up, the frequency of cyst growth (20–45%), cross-over to resection (8–11%), and progression to carcinoma (2–3%) was similar. The observed rate of developing cancer in the group that was stable even after 5 years of surveillance was 31.3 per 100,000 per year, whereas the expected national age-adjusted incidence rate for this same group was 7.04 per 100,000 per year. Because of these findings, we believe that long-term surveillance of all patients with IPMN is warranted.

SummaryOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

The management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is one that has rapidly evolved. With an improved understanding of the individual biology of the given lesion, and the increased incidental identification of these lesions, we believe a paradigm shift with respect to the management of these lesions should be away from routine resection and towards a more selective approach. This shift has been, and should continue to be, largely secondary to improvements in diagnostic modalities as well as secondary to improvements in our understanding of the natural history of these neoplasms. As our diagnostic accuracy improves, so will our ability to prescribe a treatment plan specific to the given type of neoplasm and we believe an even larger number of patients will be monitored radiographically—rather than resected. Recommendations will become not only specific to the histopathologic class of the lesion, but also specific to the individual lesions risk of progression. As our understanding of the natural history of these lesions improves we believe that the indications and the extent of resection will be further refined.

AcknowledgementsOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

None.

FootnoteOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

ReferencesOther Section

- Introduction

- SCA

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

- MCN

- IPMN

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

- Kloppel G, Kosmahl M. Cystic lesions and neoplasms of the pancreas. The features are becoming clearer. Pancreatology 2001;1:648-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gorin AD, Sackier JM. Incidental detection of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Md Med J 1997;46:79-82. [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Del CC, Targarona J, Thayer SP, et al. Incidental pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg 2003;138:427-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horvath KD, Chabot JA. An aggressive resectional approach to cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg 1999;178:269-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, et al. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg 2004;239:651-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen PJ, Jaques DP, D’Angelica M, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: selection criteria for operative and nonoperative management in 209 patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;7:970-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen PJ, D’Angelica M, Gonen M, et al. A Selective Approach to the Resection of Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas: Results From 539 Consecutive Patients. Ann Surg 2006;244:572-82. [PubMed]

- Gaujoux S, Brennan MF, Gonen M, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: changes in the presentation and management of 1,424 patients at a single institution over a 15-year time period. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:590-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Compton CC. Serous cystic tumors of the pancreas. Semin Diagn Pathol 2000;17:43-55. [PubMed]

- Linder JD, Geenen JE, Catalano MF. Cyst fluid analysis obtained by EUS-guided FNA in the evaluation of discrete cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a prospective single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:697-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strobel O, Z’graggen K, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, et al. Risk of malignancy in serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Digestion 2003;68:24-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, et al. Pancreatic cysts: a proposed management algorithm based on current evidence. Am J Surg 2007;193:749-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klimstra DS, Wenig BM, Heffess CS. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a typically cystic carcinoma of low malignant potential. Semin Diagn Pathol 2000;17:66-80. [PubMed]

- Wilentz RE, Albores-Saavedra J, Hruban RH. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Semin Diagn Pathol 2000;17:31-42. [PubMed]

- Compagno J, Oertel JE. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas with overt and latent malignancy (cystadenocarcinoma and cystadenoma). A clinicopathologic study of 41 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1978;69:573-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson LD, Becker RC, Przygodzki RM, et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasm (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of low-grade malignant potential) of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic study of 130 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, et al. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics 2005;25:1471-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sarr MG, Kendrick ML, Nagorney DM, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: benign to malignant epithelial neoplasms. Surg Clin North Am 2001;81:497-509. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zamboni G, Scarpa A, Bogina G, et al. Mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas: clinicopathological features, prognosis, and relationship to other mucinous cystic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:410-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, et al. A review of mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas defined by ovarian-type stroma: clinicopathologic features of 344 patients. World J Surg 2006;30:2236-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor of the pancreas: a historical review of the nomenclature and recent controversy. Pancreas 2001;23:12-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adsay NV, Merati K, Basturk O, et al. Pathologically and biologically distinct types of epithelium in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: delineation of an "intestinal" pathway of carcinogenesis in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:839-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terris B, Ponsot P, Paye F, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas confined to secondary ducts show less aggressive pathologic features as compared with those involving the main pancreatic duct. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1372-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yopp AC, Katabi N, Janakos M, et al. Invasive carcinoma arising in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a matched control study with conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2011;253:968-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. Ann Surg 2004;239:788-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White R, D’Angelica M, Katabi N, et al. Fate of the remnant pancreas after resection of noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:987-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvia R, Fernandez-Del CC, Bassi C, et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg 2004;239:678-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an increasingly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg 2001;234:313-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lawrence SA, Attiyeh MA, Seier K, et al. Should Patients With Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas Undergo Long-term Radiographic Surveillance?: Results of 3024 Patients Evaluated at a Single Institution. Ann Surg 2017;266:536-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]