Advance care planning in metastatic breast cancer

End-of life-care requires improvement

End-of-life care requires improvement (1-3). Since the 1990s, the inadequacy of end-of-life care has been recognized (4,5). Patient’s wishes regarding medical interventions after they lose the ability to make decisions for themselves have been poorly granted. It has been shown that there is a great dissociation between patients’ wishes about their end-of-life care and the actual medical treatment given by their care providers (6). This has been the case to the present day (7).

Breen et al. reported that conflict is more prevalent in end of life decision making than had previously been thought (8). Conflict between the medical staff and family was observed in 48% of cases, conflict among medical staff members in 48% of cases, and conflict among family members in 24% of cases. In 63% of cases, conflict about life-sustaining treatment was observed. Such frequent conflict in end-of-life treatment may result in dissatisfaction of not only the patient but also of all parties concerned if it is not appropriately managed (8). The observed conflict usually arose from a lack of communication between the patient and their care providers.

It is not rare that patients do not have a full understanding about their illness and the outcome in the end (5,9,10). The opportunity for patients to express their wishes about their end-of-life care is often lost in such cases. Seriously ill patients are too ill to think or talk about their wishes with physicians and family members (11). Patients are sometimes shown to be reluctant to discuss their disease or prognosis with physicians and tell them their preferences (12).

Physician attitudes toward seriously ill patients has not been traditionally taught in medical schools (13,14), even if most oncologists regard themselves as having an important role to play in end-of-life care (15).

What is a good death?

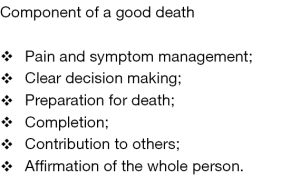

Attention on the improvement of end-of-life care is increasing. However, patients, family members and health care providers sometimes totally lack understanding about what a good death is (5). To provide good care for dying patients, we should know what really constitutes a good death. Steinhauser et al. investigated what a good death is through focus group discussions and in-depth interviews of patients, families, and health care providers (16). As a result, six major components of a good death were identified (Figure 1).

In Steinhauser’s research, physicians’ definition of a good death differed greatly from those of other groups. Physicians valued a biomedical perspective of physical symptom management the most. Physicians are taught in medical school and in textbooks that attempting to relieve physical suffering by means of medical intervention is part of their professional duty. On the contrary, patients, families and other health care professionals defined a good death as a broad range of attributes to the quality of dying. Although there is no one “right” way to die, the six major identified components may be used as a framework for understanding what patients and others value at the end of life, and what kind of end-of-life care should be given to a dying patient.

First of all, biomedical care is very critical, because well managed symptom care can allow patients and other team members to think further about end-of-life care. Improved treatment of symptoms has been shown to positively associate with the enhancement of patient and family satisfaction, functional status, quality of life, and other clinical outcomes (17,18). As is indicated in Figure 1, psychosocial and spiritual issues are as important as the management of physical symptoms for patients and families. These six components should be well understood by physicians. To this end, advance care planning (ACP) seems to play an important role, because it can clarify the wishes and hopes of a patient and family and facilitate communication among the attending team (19-22).

To have a good death, a patient should have a realistic understanding of the nature of the disease and its prognosis, as well as goals of care. The amount of time available for a patient to prepare for death should be known to the patient, the patient’s family and all involved care providers. These difficult tasks should be carried out in a way that a patient’s hope and dignity is fully respected. The process of truth telling to a patient should be carried out in a way that a patient is cared for as a whole person.

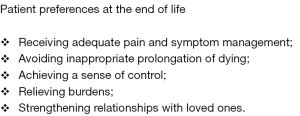

Singer et al. studied the end of life elements especially important from a patient’s perspective (5). Five elements were identified. Patients preferences at the time of being critically ill are shown in Figure 2.

Again, adequate pain and symptom control is regarded as critical (5). What is important in end-of-life care from a patient’s perspective is not a futile attempt at curative treatment, but relief of physical and psychological suffering (5). Because these preferences are very individual and may vary from patient to patient or change over time, a detailed conversation can reveal the real wishes of a patient which should then be told to all of that patient’s care providers. Outlining realistic and attainable goals is important in regards to advanced disease, because medical treatment intended to cure the disease and prolong life may no longer be beneficial but may actually be harmful (13). These processes are what ACP is all about.

ACP

ACP is defined as the process whereby patients consult with health care professionals, family members and other loved ones to make individual decisions about their future healthcare and medical treatments to prepare for when patients lose competency to express their wishes (21,23-29). ACP enables patients and their families to consider what care and treatments might or might not be acceptable, and to implement care and treatment consistent with their wishes (23,24). ACP primarily focuses on planning for the time when patients are incapable of making a decision, but it can also be applied to patients who retain capacity. Originally, ACP was implemented to complete written documents, such as advance directives (ADs), do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and do-not-hospitalize (DNH) orders. Nowadays, the focus of ACP is regarded as not only about the completion of written forms but also on the social process of communication between patients and care providers (21).

ACP has been receiving increasing attention since the 1990s (23). Its clinical effects from various standpoints have been investigated. The “Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment” (SUPPORT) failed to show any beneficial effects of ACP intervention on expected outcomes, such as shortening the stay in ICU or avoiding unwanted mechanical ventilations (4). ACP is sometimes stressful for patients, and implementation of ACP is less effective in those cases. The way to decrease stress caused by implementation of ACP should be taken (4).

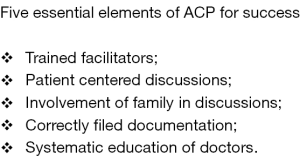

However, more recent studies have shown that ACP is able to improve consistency with patients’ end-of life-wishes and patients’ and their families’ satisfaction with care (3,19,26,28). ACP was also shown to reduce family stress, anxiety and depression. Detering et al. investigated the beneficial impact of ACP in elderly patients in a randomized control trial (3). Five elements were revealed to be essential for ACP to be successful in fulfilling patients’ wishes in end-of-life care (Figure 3). According to their analysis, the failure of the SUPPORT study to show the beneficial effects of ACP was due to a lack of four of the elements other than trained facilitators (3).

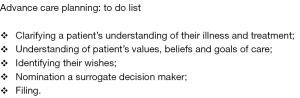

Again, what is important in ACP is not a writing of ADs, but a process of conversation among concerned parties (Figure 4) (1,30). Through such discussion, everyone can understand the wishes of the patient in end-of-life care and their background behind those wishes. Mutual understanding shared by family members and health care providers results in concordance and respect of patient’s treatment wishes.

Indeed, White et al. and others have reported that the involvement of family members in a process of shared decision making is important because they commonly misunderstand information about the prognosis and the results of treatment even after a physician-family conference (3,20).

There are several barriers to be overcome in the implementation of ACP (3,26,27). Physicians are often not accustomed to confronting dying patients and are not taught how to support suffering patients in end-of-life care (13,31). They are well trained to explain the detailed procedures of medical interventions but information regarding outcome prospects and the post-treatment effects on daily life is often lacking. Patients have to face cruel fate for the first time and tend to have unrealistically high hopes for a cure by medical intervention. Several studies have demonstrated that cancer patients’ understanding of their prognosis is imperfect and that they tend to overestimate the probability of cure or life extension.

Weeks et al. reported that 69% of stage IV incurable lung cancer patients and 81% of stage IV incurable colorectal cancer patients believed their chemotherapy to be curative (32). Therefore, only 20–30% of patients who had incurable cancers had an accurate understanding of their disease. Both patients and physicians contributed to this misunderstanding (32). This kind of misunderstanding is an obstacle to end-of-life planning. If patients do not understand their prognoses or the effect of medical interventions accurately, then their treatment decisions may not reflect their true values. Patient estimates of their survival was revealed to strongly influence their treatment decisions (33).

Are physicians ready to talk about end of life?

There are many reasons why patients with advanced diseases receive inadequate care (13). Most of the reasons are related to the attitude of medical practitioners. Medical interventions are mostly aimed at curing illness and prolonging life, rather than on improving the quality of life and relieving suffering. Most medical schools are not ready to educate students how to take good care of dying patients (13,14).

Atul Gawande wrote an anecdote about a cancer patient named Mr. Lasaroff in his book Being Mortal (34).

“I learned about a lot of things in medical school, but mortality wasn’t one of them.”

Mr. Lazaroff was diagnosed with metastatic cancer with spinal cord compression. He decided to have an operation to remove his tumor. The operation was technically successful but he never recovered from the procedure. He was on a ventilator in the ICU. On the 14th day after the operation, Atul Gawande removed his breathing tube and Mr. Lazaroff’s breathing stopped and his heartbeat faded away.

After a decade, Atul Gawand recalls: “What strikes me most is not how bad his decision was but how much we all avoided talking honestly about the choice before him. We had no difficulty explaining the specific dangers of various treatment options, but we never really touched on the reality of his disease. His oncologist, radiation therapist, surgeons, and other doctors had all seen him through months of treatment for a problem that they knew could not be cured. We could never bring ourselves to discuss the larger truth about his condition or the ultimate limits of our capacities, let alone what might matter most to him as he neared the end of his life. If he was pursuing a delusion, so were we.”

Sullivan et al. studied the status of end-of-life care medical education in the U.S. (14). Their survey showed that students and residents in the U.S. feel unprepared to provide many key components of good care for the dying. At the same time, faculty and residents were unprepared to teach those important issues to their juniors. They concluded that the current educational practices and institutional culture in U.S. medical schools do not support adequate end-of-life care. Tom Hutchinson wrote in his book that “whole person care” should be taught in medical schools as a new paradigm for the 21st century (35).

It had been observed that oncologists who view end-of-life care as an integral part of their job and discuss these issues with their patients, had more satisfying experiences and less burn out. Implementation of ACP with multidisciplinary providers is expected to change the end-of-life care scene in the near future.

ACP and metastatic breast cancer (mBC)

Breast cancer is the second most common form of cancer among women worldwide (36). The population suffering from mBC is distributed from a fairly young age up to the elderly. In spite of this broad distribution, there is insufficient public knowledge about the prognosis for patients with mBC (36). In most countries surveyed, a majority (52–76%) believed that mBC is curable. It may be partially because life expectancy after the diagnosis of mBC is longer than other type of cancers. Information about the development of new drugs tends to promote expectations of a cure. In spite of the prevalence of Her2-positive breast cancers, improvement in the overall survival of mBC has been small and mBC is still a difficult to cure disease (37). Due to the above factors, most mBC patients may not think about end-of-life care until the last moment.

Ozanne et al. reported that 75% of women with mBC had gathered information about AD and 66% of them had actually written an AD (12). However, only 14% of their care providers were aware of the presence of the AD. Patients were more than three times as likely to talk about and share written plans with friends and family than with their care providers. Whether this tendency is specific to mBC or not is unclear. Facilitation of frank discussion about end-of-life care between physicians and patients is needed in order to provide quality patient care from the standpoint of the implementation of ACP (12).

While patients prefer honesty from their health care providers, how best to communicate with patients about these issues without compromising their sense of hope and optimism remains a significant challenge for those providers (3). More detailed research is needed to implement ACP in an efficacious way for mBC patients.

ACP and end-of-life care

End-of-life care for seriously ill patients should be improved. To accomplish this, we should foster competent facilitators, establish an organized system to support the introduction of ACP and promote physicians’ understanding and support of ACP. An organized ACP system can and should be routinely used for a targeted end-of-life population. Education about end-of-life care and a culture change in medical schools should be carried out and this can be catalyzed by the widespread introduction of ACP. Patients and health care providers should regard ACP as a standard part of end-of-life care.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Romer AL, Hammes BJ. Communication, trust, and making choices: advance care planning four years on. J Palliat Med 2004;7:335-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Morrison EW, Glickman DF. Physician reluctant to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation if potential barriers. Arch intern Med 1994;154:2311-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 1995;274:1591-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients' perspectives. JAMA 1999;281:163-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winzelberg GS, Hanson LC, Tulsky JA. Beyond autonomy: diversifying end-of-life decision-making approaches to serve patients and families. J AM Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1046-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drazen JM, Desai NR, Green P. Fighting on. N Engl J Med 2009;360:444-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Abbott KH, et al. Conflict associated with decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:283-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perkins HS. Controlling death; the false promise of advance directives. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:51-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1061-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Appelbaum PS. Assessment of Patient’ Competence to Consent to Treatment. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1834-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozanne EM, Partridge A, Moy B, et al. Doctor-patient communication about advance directives in metastatic breast cancer. J Palliat Med 2009;12:547-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Meier DE. Palliative Care. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2582-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD. The Status of Medical Education in End-of-life Care, A National Report. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:685-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jackson VA, Mack J, Matsuyama R, et al. A qualitative study of oncologists' approaches to end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2008;11:893-906. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:825-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bookbinder M, Coyl N, Kiss M, et al. Implementing national standards for cancer pain management: program and evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:334-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Magaziner J, McLaughlin MA, et al. The impact of post-operative pain on outcomes following hip fracture. Pain 2003;103:303-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, et al. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:477-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White DB, Braddock CH 3rd, Bereknyei S, et al. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:461-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sudore RL, Hillary DL, John JY, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821-32.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014;28:1000-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer PA, Robertson G, Roy DJ. Bioethics for clinicians: 6. Advance care planning. CMAJ 1996;155:1689-92. [PubMed]

- National End of Life Care Program. Dying Matters, University of Nottingham Planning for your future care. Available online: https://www.dyingmatters.org/page/planning-ahead

- Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance Directives and Outcomes of Surrogate Decision Making before Death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1211-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones L, Harrington J, Barlow CA, et al. Advance care planning in advanced cancer: can it be achieved? An exploratory randomized patient preference trial of a care planning discussion. Palliat Support Care 2011;9:3-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Billings JA, Bernacki R. Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the Goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:620-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin RS, Hayes B, Gregorevic K, et al. The Effect of Advance Care Planning Interventions in Nursing Home Residents: A Systemic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:284-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lovell A, Yates P. Advance Care Planning in palliative care: a systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing its uptake 2008-2012. Palliat Med 2014;28:1026-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- . . Available online: https://respectingchoices.orgRespecting Patient Choices Program. 2018.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:651-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 1998;279:1709-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gawande A. Being Mortal: Illness, Medicine and What Matters in the End. Profile Books Ltd., 2015.

- Hutchinson TA. editor. Whole Person Care: Transforming Healthcare. New York: Springer, 2011.

- Cardoso F, Beishon M, Cardoso MJ, et al. MBC General Population Survey: Insights into the general public’s understanding and perceptions of metastatic breast cancer (mBC) across 14 countries. ESMO 2015. Available online: http://www.abcglobalalliance.org/pdf/Decade-Report_Full-Report_Final.pdf

- Gobbini E, Ezzalfani M, Dieras V, et al. Time trends of overall survival among metastatic breast cancer patients in the real-life ESME cohort. Eur J Cancer 2018;96:17-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]