Transitions in palliative care: conceptual diversification and the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care

Introduction

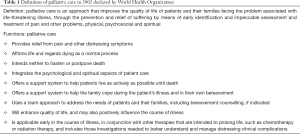

In 2002, WHO defined palliative care as described in Table 1. This definition focuses on “relieving pain and improving QOL” (quality of life), and the palliative care approach based on this definition is summarized by the following five ideas:

- QOL focused approach: emphasize QOL rather than treatment and curing disease;

- Whole-human approach: identify individuals who need palliative care as “more than patients”, such as those who need medical as well as social support;

- Care that encompasses both the patient and those involved with the patient (particularly caregivers): people surrounding the patient, such as “family and friends”, are also given similar care;

- Respect patient autonomy and choice: for example, clarify what the patient wishes about choosing a place to recuperate and where live out their last days, and support the realization of those goals;

- Support people through frank and thoughtful discussions on difficult subjects: how to communicate prognosis of patients with terminal illnesses.

Full table

Palliative care is classified into several categories for convenience and depending on the timing offered, but this approach is the basis of palliative care.

How has this approach been formed and developed? First, we outline the concepts formed during the development of palliative care while briefly reviewing its history.

The formation and development of hospice care

The modern hospice movement began in the UK in the 1960s. Cicely Saunders, a 20th century British nurse and social worker, was responsible for the formation of the core tenets applied in hospices around the world through her experiences at St Luke’s Home. In these tenets of hospice care, the concepts of “total pain”, including physical, spiritual, and psychological discomfort; the proper use of opioids for patients with physical pain; attention to the needs of “family members and friends who provide care for the dying” among other ideas are included, and continue to persist in the ethos of the palliative care approach today. St Christopher’s, which Saunders founded in the UK in 1967, is widely known as the first modern hospice. In this hospice ward, patients with extremely close end of life who had progressive incurable illnesses were hospitalized and received hospice care until death. Hospices then spread around the world, taking the form of a sort of medical revolution, a social movement that would come to be known as the hospice movement.

The formation and development of palliative care

The term “palliative care” was first used by a Canadian physician named Balfour Mound in 1974 in a treatment setting aimed at symptom relief (1). He had adopted many principals of British hospice movement to acute care hospitals in Canada first and then around the world. In this palliative care program, three main features were developed, namely, multidimensional assessment and management of severe physical and emotional distress; interdisciplinary care by multiple disciplines in addition to physicians and nurses; emphasis on caring not only the patients but also for their families (2). During the development and popularization of palliative care based on the hospice care movement, many aspects of the latter were retained.

Initially, when palliative care was introduced into acute hospital care, the palliative care unit was in an isolated position, as if a separate hospice attached to a hospital. There was a limit to the number of patients that could be handled in palliative care wards, and it is recognized that there was a need for palliative care for patients before they became unresponsive to treatment, and patients other than these were also admitted to palliative care wards and a palliative care team was launched to provide care. The purpose of a palliative care team is to consider the difficult problems encountered in palliative care and to support other healthcare workers perform their daily duties more effectively by providing professional support based on knowledge and technology. Multidisciplinary care utilizing multiple roles is one feature of this care approach, and includes physicians, nurses, public health nurses, medical social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, nutritionists, rehabilitation professionals, nursing care professionals, care managers, chaplains, among others.

Supportive care

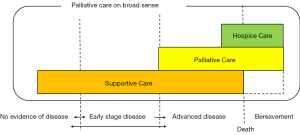

Supportive care is a major feature that concerns not only the disease-related symptoms targeted by palliative care, but also acts as a new medical discipline aiming to provide predominantly cancer patients with support for the management of “treatment-related effects” (1). Supportive care includes subjects at earlier stages of illness, patients who did not develop advanced cancer or become nonresponsive to treatment, as well as patients receiving care in areas such as psychosocial care, spiritual care, communication, and survivorship care. Supportive care was continuously provided to patients and families whose disease condition progressed and became subject to palliative and hospice care (Figure 1).

Palliative care classification models

As mentioned previously, palliative care has developed while its core concepts have diversified. In addition, to respond to the complex needs arising during cancer treatment, various palliative care delivery systems have been attempted. This sometimes resulted in confusion. When simply saying, “palliative care”, there were cases where people actually intended to provide hospice care, supportive care, or some other form of care. To avoid this kind of confusion, it’s important to consistent by using the palliative care classification model. There are various modes of care depending on the time of delivery and the medical systems used, but these can be roughly classified into two models, described below.

Time-based model

One concept for classifying the modes of palliative care delivery developed thus far is the “time-based model” (Figure 1) (3). This model can be thought of as dividing care into “supporter care”, “palliative care”, and “hospice care” by time axis (stage of cancer). Supportive care is the basis for this model and should be offered from the initial stages of disease, palliative care calls for more specialized symptomatic relief for advanced cancers, and hospice care is concerned with end of life care (primarily during the last 6 months of life).

Provider-based model

Another classification is the “provider-based model” (4). This model focuses on the provision of palliative care according to the level of patient complexity and the setting (Figure 2). Primary palliative care is provided by oncologists and primary care providers. Patients with more complex care needs will be referred to secondary palliative care, in which specialist palliative care teams see patients as consultants. In tertiary palliative care, the palliative care team functions as the attending service, providing care for patients with the most complex supportive care needs, such as in an acute palliative care unit.

Regardless of the classification, there has also been a movement in recent years to integrate these care models seamlessly, and it is believed that the boundaries between these conceptual models will become more ambiguous in the future. Careful attention is required as confusion over the terminology can occur.

Obstacles in the provision and delivery of palliative care

To date, generally care from the specialist palliative care team has been provided “on-demand” when deemed necessary by the primary team. However, due to some barriers, there have been tendencies for “late referrals”. Causes of “late referrals” on the medical side are believed to include medical staff’s fear of patient response (5), misunderstanding of the role of palliative care (6,7), and physicians’ uncertainty about the appropriate time to refer patients (8); system-related issues include advancements in the field of medicine in recent decades, which has allowed for greater knowledge on cancer and has thus promoted the introduction of novel effective systemic therapies, such as targeted drugs, immunotherapy, and new chemotherapeutic agents (9,10); issues on the patient side includes stigmatization of patients and/or their families (11), among other issues, and as a result, the underdiagnosis of pain as well as worse pain management (12), lower family satisfaction (13-15), increased caregiver burden (16), and negative impact on the management of various physical and psychosocial symptoms and quality indicators of end-of-life care compared with timely access (17) have been reported. The issue of late referrals, conversely, suggests the possibility of improving clinical efficacy by appropriately accelerating the timing of interventions. Therefore, proper delivery of palliative care has been considered to meet the needs of patients and families.

A screening was attempted to address the problem of late referrals, but the screening itself was not able to solve the problem of false positives, cost efficacy was left unclear, and what to do after screening was seen as more important than the screening itself. As such, the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care to be shown later is now recommended.

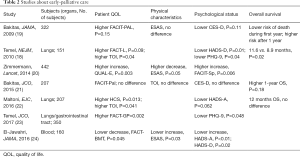

Advocacy for early palliative care

In following from the background presented in the previous section, discussion of the appropriate timing of specialist palliative care intervention has become more active, and in 2010, Temel et al. announced a clinical trial concerning “early palliative care” (18) in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The breakthrough point of this study was to provide specialist palliative care during anticancer therapy for patients with advanced cancer, such that the period of time when anti-cancer drugs were used was shorter for subjects in the palliative care group, and nonetheless, extension of survival prognosis was observed. Various subsequent reports on the effects of specialist palliative care with similar “advanced cancer” patients were also published (Table 2). In these studies, “specialist palliative care” was provided systematically rather than on an on-demand basis for all “patients with distant metastasis, locally advanced/recurrent tumors”, and as a result, some studies reported not only improved patient QOL but also the clinical effect of extended survival prognosis. Therefore, many studies recommend that “specialist palliative care” be provided to “advanced cancer patients”.

Full table

However, these studies are not completely consistent with respect to the provider of “specialist palliative care”, the timing of intervention, the object, and so on. For the provider, palliative care physicians and/or palliative nurses at minimum (20,25,26) said that members of the palliative care team included occupations such as social worker, chaplain, and/or rehabilitation specialists. Ferrell et al. (27) conducted an interventional study of specialist palliative care patients with non-small cell lung cancer patients of all stages, and although improvement of QOL, physical symptoms, and psychiatric symptoms were observed, no extension of survival prognosis was observed. Data concerning intervention timing and knowledge of interventions with patients other than advanced cancer patients are meager, and there is currently no consensus view.

In Japan, to promote appropriate palliative care for cancer patients in a framework not limited to advanced cancers, Japanese policy was affected the definition of palliative care that expanded the subject patients by WHO in 2002, and recommended “palliative care from the time of diagnosis”. Regarding its content, it has listed pain and emotional support associated with cancer incidents, information on treatment, and self-management education on possible future suffering, which corresponds to supportive care in the time-based model conceivable. Therefore, “palliative care from the time of diagnosis” in Japan is considered to mean the provision of supportive care from the time of diagnosis for all cancer patients and their families (not just patients with advanced cancers). However, “primarily at hospitals centering on core hospitals, it plan to suitably arrange psychiatric oncologists, professional nurses, certified caregivers, social workers, and clinical psychologists specialized in cancer nursing, and improve the capacities of palliative care teams and outpatient palliative care functions” and it became possible to interpret that the main stakeholders of the “palliative care from the time of diagnosis” recommended by the government will be provided by these staff. This has spread the misunderstanding that the goal is to provide supportive care from providers who should be primarily responsible for secondary palliative care in the provider-based model. To avoid such confusion, it is important to organize care elements such as “target patient” and “medical treatment details”, etc. using classifications models such as the time-based and provider-based models.

Challenges in providing palliative care interventions for all cancer patients

Expanding the scope of specialist palliative care can also improve QOL of interventional patients, but several problems have been pointed out in expanding target only, According to Quill et al. (28), “First, the increasing demand for palliative care will soon outstrip the supply of providers. Second, many elements of palliative care can be provided by exiting specialist or generalist clinicians regardless of discipline; adding another specialty team to address all suffering many unintentionally undermine exiting therapeutic relationships. Third, if palliative care specialists take on all palliative care tasks, primary care clinicians and other specialists may begin to believe that basic symptom management and psychosocial support are not their responsibility, and care may become more fragmented.” In the same report by Ferrell et al. mentioned previously, “Specialist palliative care provided to all cancer patients including those with early-stage cancers is difficult from the perspective of medical resources.”

In order to appropriately provide palliative care to all cancer patients, it is necessary to consider adapting the care provision model in line with medical resource limitations.

Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care

Based on this background and study findings, the concept of “integrating palliative care into standard oncology care” is now recommended. Based on the aforementioned provider-based model (Figure 2), this form of care would be, in essence, a combination of primary palliative care performed by oncology care staff, secondary palliative care, and tertiary palliative care performed by palliative care specialists performed by other departments, and providing such services in a consistent manner while working to eliminate barriers identified is recommended. As primary palliative care is carried out by oncology care staff, while this is natural and efficient, diagnosis and responses to unexpected symptoms may be delayed. Although secondary and tertiary palliative care can address multiple issues, it is necessary to start with the formation of treatment relationships, and efficiency can deteriorate as a result of involvement of multiple occupations. “Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care” can be expected to complement the advantages and disadvantages of the primary palliative care, secondary palliative care, and tertiary palliative care described above, and by implementing this, improved QOL, quality of end-of-life care, decreased rates of depression, illness understanding, and patient satisfaction have been demonstrated (18,20,25,26).

The provisional clinical opinion on the “Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care” (29) was made public in the 2012 by American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), of which Guideline (27) was updated in 2017. The guideline states that, “Inpatients and outpatients with advanced cancer should receive dedicated palliative care services, early in the disease course, concurrent with active treatment”, and strongly recommends “Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care”. This applies not only to care at the terminal stage after anticancer treatments, referred to as hospice care in the time-based model, but also to progressive cancers which are often complicated even during anticancer therapy, and expanding professional palliative care to these patients as well is recommended.

In the ASCO guidelines (27), this role is described as, “rapport and relationship building with patients and family caregivers; symptom, distress, and functional status management (e.g., pain, dyspnea, fatigue, sleep disturbance, mood, nausea, or constipation); exploration of understanding and education about illness and prognosis; clarification of treatment goals; assessment and support of coping needs (e.g., provision of dignity therapy); assistance with medical decision making; coordination with other care providers; provision of referrals to other care providers as indicated”, and not only patients but also families [a family caregiver is defined as either a friend or relative who the patient describes as the primary caregiver; it may be someone who is not biologically related (30)], and control of mental and physical symptoms, patient education, decision-making support, and cooperation among supporters are also included. While it is possible that the provider may also be on the primary oncology team, this type of care should be provided mainly by a member of the palliative care team that is comprised of specialists from other fields able to achieve the same level of effect as in the study.

In addition, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has been recommending this mode of care internationally since 2003 through its ESMO Designated Centers of Integrated Oncology & Palliative Care program targeting facilities meeting a high standard with respect to the integration of medical oncology and palliative care.

However, because clinical environments differ by country, specific approaches to integrating palliative care into standard oncology care are still under discussion. The ASCO Guidelines (27) currently recommend targeting patients with advanced cancer and caregivers of patients with early or advanced cancer, and regarding specific care measures and intervention periods, the Guidelines state, “For newly diagnosed patients with advanced cancer, the Expert Panel suggests early palliative care involvement within 8 weeks of diagnosis”, “For patients with early or advanced cancer for whom family caregivers will provide care in the outpatient setting, nurses, social workers, or other providers may initiate caregiver-tailored palliative care support, which could include telephone coaching, education, referrals, and face-to-face meetings. For family caregivers who may live in rural areas and/or are unable to travel to clinic and/or longer distances, telephone support may be offered”. However, no specific recommendations beyond this were offered based on this evidence. Hui et al. reported on the integration of oncology and palliative care, and wrote, “tremendous heterogeneity in healthcare systems, patient population, resource availability, clinician training, and attitudes and beliefs toward palliative care worldwide, it is important to emphasize that no one model will offer the solution for all.” (4).

Characteristics of palliative care, and early palliative care in breast cancer

Breast cancer patients tend to have many problems because of (I) breast cancer usually emerge in comparatively youth whose social activity is energetic; (II) gynecomorphous appearance changes owing to surgery, chemotherapy, and disease itself; (III) hormone therapy effects sex hormone; (IV) survival time after having cancer tends to be long compared to another type of cancer. So, following problems would occur not only having treatment but also post-treatment, and we should keep in mind that it affects for a long time and influences patients in palliative care too.

Esthetic effects

Patient’s appearance tends to be changed in the course of struggle against disease. Montazeri et al. reported that patients who undergone surgery have lower body image and sexual function compared to who didn’t (31). Chemotherapy occasionally causes nausea, weight loss, hair loss, and rough skin and nail, which makes severe changes of appearance. Esthetic problems not only make patients feel pain by itself, but also it may affect their social activities, continuation and returning to work (32,33). Their self-esteem, concern of sensuality and sexuality may fall (34,35). And they suffer from changing a look by people around different from what they used to be because of changing appearances (36).

Sexuality effects

A cross-sectional survey of women with diagnosed with breast cancer prior to age 50 found premature menopause, fertility, sexual dysfunction, and body image to be the greatest concern, along with frequently bothersome symptoms of hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and decreased libido (37).

Dyspareunia was reported by more than 50% of women receiving aromatase inhibitors and by 31.3% of those receiving tamoxifen (38). Women who had received chemotherapy reported higher levels of sexual discomfort even years after completion of chemotherapy (39). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, very effective means of reducing hot flashes, can have significant sexual side effects (40). In spite of those situation, physicians often fail to initiate conversations about such symptoms, and patients frequently feel uncomfortable broaching the topic of sexual functioning, even when physicians did initiate conversations regarding sexuality, the discussion was often perceived as inadequate (41,42). Although sexuality effects are very significant, reports about the problem of sexual function for patients with progressive or relapse are limited. Taylor suggested that physicians should talk about sexual dysfunction at the beginning of treatment and consequently patients report those problems later on, when they occur (43). It not only contributes to patient’s QOL but it is also useful for future data accumulation.

Psycho-social effects

Women with metastatic breast cancer are also at risk for emotional distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as existential distress and loneliness. In cross-sectional studies, almost one-third of women with metastatic breast cancer met DSM-IV criteria for a depressive disorder and 6% met criteria for an anxiety disorder. Demographic and medical correlates of distress among metastatic breast cancer patients have been identified. Younger age and the progression of the disease toward a terminal stage have been associated with worse psychological adjustment. Among women with breast cancer recurrence, most of whom had metastases, distress peaked around the time of diagnosis and then declined in the year thereafter (44).

It has been suggested that metastatic breast cancer also correlates with low level of the global QOL (45). QOL is good in this population of women living long term with metastatic breast cancer, there is a subset of women who are dealing with significant anxiety and depression, and a larger group who are experiencing burdensome sadness, hopelessness, and apprehension about their disease (46).

Group psychosocial support is useful for improving mood and the perception of pain in patients with metastatic breast cancer (47). Although Spiegel reported that psychosocial group therapy improves the survival rate of patients with metastatic breast cancer (48), it has come to the conclusion that it does not contribute to survival rate by a number of follow-up trials.

Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care in breast cancer

The effect of the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care for only breast cancer patients has not been reported on yet. However, subjects of several prior studies included breast cancer patients (20,49-52).

Reported effects include improved QOL, less depression, less chemotherapy needed during the last 6 weeks of life, and longer survival compared with the traditional care model.

Further reports focusing on only breast cancer are expected in the future.

Summary

Patient prognosis has improved in recent years with the advent of oral anticancer drugs and molecularly-targeting drugs, and cancers become chronic in more cases. Treatment/care have shifted from hospitals to outpatient clinics, and mid- to long-term support is now required. To improve the QOL of patients and their families, it is important to be able to receive palliative care as appropriate in a variety of situations.

Kaasa et al. (53) considered future topics on this issue, such as, “What is the optimal content of palliative care? What level of palliative care is needed for a clinically significant difference? What is the optimal way of combining oncological care with palliative care, i.e., the optimal level of integration?” As a practical matter, it is difficult for all hospitals to provide temporary palliative care for all patients with specialized staff (not limited to advanced cancer). To obtain the best outcomes in actual clinical practice, we await future reports concerning how to determine the specific patients who should be targeted for care and how best to treat them, as well as how best to handle patients with early cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for the helpful comments.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Yennurajalingam S, Bruera E. editors. Oxford American Handbook of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care. Oxford University Press; 1 edition. August 16, 2011.

- Lutz S. The history of hospice and palliative care. Curr Probl Cancer 2011;35:304-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:659-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:89-98. [PubMed]

- Smith CB, Nelson JE, Berman AR, et al. Lung cancer physicians' referral practices for palliative care consultation. Ann Oncol 2012;23:382-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson C, Paul C, Girgis A, et al. Australian general practitioners' and oncology specialists' perceptions of barriers and facilitators of access to specialist palliative care services. J Palliat Med 2011;14:429-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knapp C, Thompson L, Madden V, et al. Paediatricians' perceptions on referrals to paediatric palliative care. Palliat Med 2009;23:418-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wirth A, Smith JG, Ball DL, et al. Symptom duration and delay in referral for palliative radiotherapy in cancer patients: a pilot study. Med J Aust 1998;169:32-6. [PubMed]

- Dos-Anjos CS, Candido PB, Rosa VD, et al. Assessment of the integration between oncology and palliative care in advanced stage cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1837-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faguet GB. Quality end-of-Life cancer care: An overdue imperative. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;108:69-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016;188:E217-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akashi M, Yano E, Aruga E. Under-diagnosis of pain by primary physicians and late referral to a palliative care team. BMC Palliat Care 2012;11:7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita T, Akechi T, Ikenaga M, et al. Late referrals to specialized palliative care service in Japan. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2637-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita T, Miyashita M, Tsuneto S, et al. Late referrals to palliative care units in Japan: nationwide follow-up survey and effects of palliative care team involvement after the Cancer Control Act. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:191-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, et al. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: length of stay and bereaved family members' perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:120-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Costantini M, Silber E, et al. Evaluation of a new model of short-term palliative care for people severely affected with multiple sclerosis: a randomised fast-track trial to test timing of referral and how long the effect is maintained. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:769-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 2012;17:1574-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall'Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2016;65:61-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care in Patients With Lung and GI Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:834-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. Effect of Inpatient Palliative Care on Quality of Life 2 Weeks After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;316:2094-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:75-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2319-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update Summary. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:119-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun V, Grant M, Koczywas M, et al. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for family caregivers in lung cancer. Cancer 2015;121:3737-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008;27:32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maunsell E, Brisson C, Dubois L, et al. Work problems after breast cancer: an exploratory qualitative study. Psychooncology 1999;8:467-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luoma ML, Hakamies-Blomqvist L. The meaning of quality of life in patients being treated for advanced breast cancer: a qualitative study. Psychooncology 2004;13:729-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carpenter JS, Brockopp DY. Evaluation of self-esteem of women with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 1994;21:751-7. [PubMed]

- Freedman TG. Social and cultural dimensions of hair loss in women treated for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 1994;17:334-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lemieux J, Maunsell E, Provencher L. Chemotherapy-induced alopecia and effects on quality of life among women with breast cancer: a literature review. Psychooncology 2008;17:317-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Psychosocial problems among younger women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2004;13:295-308. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baumgart J, Nilsson K, Evers AS, et al. Sexual dysfunction in women on adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer. Menopause 2013;20:162-8. [PubMed]

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:39-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:259-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anllo LM. Sexual life after breast cancer. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:241-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Male DA, Fergus KD, Cullen K. Sexual identity after breast cancer: sexuality, body image, and relationship repercussions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2016;10:66-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor CE, Meisel JL. Management of Breast Cancer Therapy-Related Sexual Dysfunction. Oncology (Williston Park) 2017;31:726-9. [PubMed]

- Mosher CE, Johnson C, Dickler M, et al. Living with metastatic breast cancer: a qualitative analysis of physical, psychological, and social sequelae. Breast J 2013;19:285-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alacacioglu A, Yavuzsen T, Dirioz M, et al. Quality of life, anxiety and depression in Turkish breast cancer patients and in their husbands. Med Oncol 2009;26:415-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meisel JL, Domchek SM, Vonderheide RH, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2012;12:119-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1719-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet 1989;2:888-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:753-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dyar S, Lesperance M, Shannon R, et al. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: results of a randomized pilot study. J Palliat Med 2012;15:890-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency Department-Initiated Palliative Care in Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2016. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rugno FC, Paiva BS, Paiva CE. Early integration of palliative care facilitates the discontinuation of anticancer treatment in women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2014;135:249-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaasa S, Loge JH. Early integration of palliative care-new evidence and old questions. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:280-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]