Central nervous system cancers in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: where does Lebanon stand

Introduction

Cancer constitutes the second most common cause of mortality in the world, falling short only to cardiovascular diseases (1,2). Around 1 out of 6 deaths is due to cancer (2). Brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors are estimated to be the 10th leading cause of death in the United States (3).

CNS cancers may be divided into primary or secondary. Primary cancers are cancers that originate in the nervous tissue, including meninges, whereas secondary cancers are masses that have arrived to the nervous tissue via metastasis from another location (4,5). The WHO identifies four different staging levels for CNS cancers, starting from grade I tumors which are the least biologically aggressive and ending with grade IV tumors which are the most biologically aggressive (6). The most frequently stumbled upon CNS tumors are gliomas which may present in any of the four mentioned grades (7).

CNS tumors are rare but very deadly cancers. This causes increased difficulty in determining potential risk factors in the population for these neoplasms. The difficulty to cure patients from these tumors is their protected nature of their brains. All potential treatment plans which include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation carry increased morbidity for patients and even incomplete cure (8).

Lebanon is a developing country in the Middle East and North African (MENA) region with a population of around 6,000,000 individuals as of 2016 (9,10). The Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) of Lebanon has established a database for the capture of new cases cancers known as the National Cancer Registry (NCR) of Lebanon. The cases collected and added to this registry are gathered from hospital registries, physician reports and public and private laboratories. The most recent data found on the NCR are those from 2005 up to 2015 (11).

This study aims to analyze the 11-year incidence rates of CNS cancers in Lebanon and draw comparisons to countries in the MENA region and other countries from around the world. This study will also attempt to discuss risk factors that may help explain the trend of CNS tumors incidence in Lebanon.

Methods

Data extraction

Data and records of Lebanese cases were extracted from the NCR which is part of the official website of the MoPH. These cases were then classified according to gender, age group, and year of incidence. All non-Lebanese ASR(w)s and age-specific incidence rates were extracted from two online databases, Cancer Incidence in Five Continents CI5XI (12) and CI5Plus (13). All countries from the MENA region with available data were included in this study. This study does not require any institutional review board (IRB) approval as the data is deidentified and publicly available on the mentioned websites.

Data processing and analysis

Age-standardized and age-specific incidence rates were calculated for the purpose of this study. The age-standardized incidence rate [ASR(w)] is a weighted average of the age-specific incidence rates per individual in the equivalent age groups of a standard population. Standardization is of extreme importance when we want to compare different populations and countries which have different age structures. The World Standard Population is the most frequently used standard population. It is calculated by drawing from a pooled population of many countries. In this study, we used the ASR(w) calculated using Ferlay’s modified world population as the reference population (14). The ASR(w) and age-specific incidence rates were calculated based on the data available in the Lebanese NCR for the years 2005–2015 (inclusive) and were expressed per 100,000 population. The age specific incidence rate is the number of new cancer cases that occurred during a specific period of time in a population of a specific age and sex group, divided by the number of midyear population of that sex and age group. The calculated ASR(w)s and age-specific incidence rates were then compared with ASR(w)s and age-specific incidence rates from different MENA and non-MENA countries. The ASR(w)s and age-specific incidence rates that we retrieved and calculated were then analyzed using the “Joinpoint regression analysis”. Annual percent changes (APC) of CNS cancer incidence over the years of the study [2005–2015] were calculated using the Joinpoint regression model. Statistical analysis was done using Joinpoint 4.7.0.0 with a significance level set at greater than 0.05.

Results

Overview

In Lebanon, 2,309 CNS cancer cases were reported between 2005 and 2015. Males and females accounted for 57.3% (1,324 cases) and 42.7% (985 cases), respectively. Incidence was generally higher in men than in women, with a male to female ratio of 1.3. CNS cancers were the 11th most common cancers in Lebanon and accounted for 2% of all newly diagnosed cancers. The average age of CNS cancers patients was around 44 years and 12% of patients were above 70 years old. Males had on average 120 new cases per year, while females had 90 new cases.

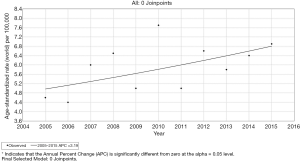

Incidence rates in Lebanese males

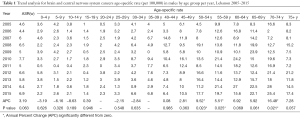

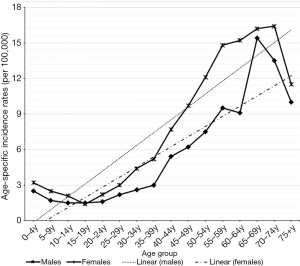

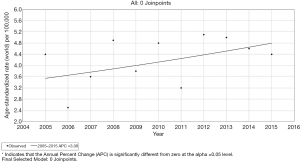

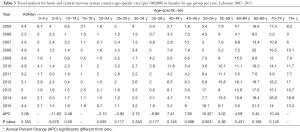

The average CNS cancers ASR(w) over the period studied was 5.9 per 100,000. The rates fluctuated between 4.4 and 7.7 per 100,000. The APC of CNS cancers incidence rate has insignificantly increased by 3.19% between 2005 and 2015 (Figure 1). The APC of CNS cancers age-specific rates has significantly increased for the age groups 50–54 (P=0.02; 95% CI, 1.6–18), 55–59 (P=0.03, 95% CI, 0.8–10.4), and 70–74 years (P=0.02, 95% CI, 3–31.8) (Table 1). CNS cancers were more common among males younger than 9 years and older than 30 years compared to other age groups. The incidence of these cancers increased with age (R2=0.83), with a maximum of 16.4 per 100,000 in males of the 70–74 years age group (Figure 2).

Full table

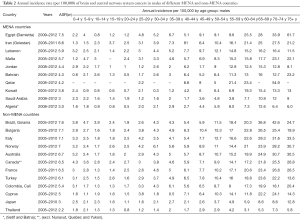

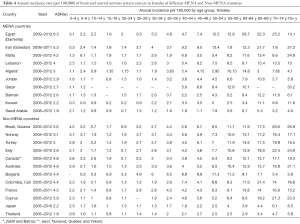

The CNS cancers ASR(w) among Lebanese males (5.7 per 100,000 between 2005 and 2012) came third after Egypt (Damietta) and Iran (Golestan province) when compared to other MENA countries. However, it was among the lowest when compared to Non-MENA countries like Brazil and Bulgaria (Table 2).

Full table

Incidence rates in Lebanese females

Between 2005 and 2015, the average CNS cancers ASR(w) was 4.2 per 100,000. The rates fluctuated between 2.5 and 5.1 per 100,000. The APC of CNS cancers ASR(w) had insignificantly risen by 3.08% during the studied period (Figure 3). The APC of CNS cancers age-specific rates has significantly increased in the 50–54 years age group only (P=0.003; 95% CI, 6.3–25) (Table 3). CNS cancers were more common among females younger than 9 years and older than 40 years compared to other age groups. The incidence rate of CNS cancers increased with age (R2=0.8), with a maximum of 15.4 per 100,000 in females of the 65–69 years age group (Figure 2).

Full table

When compared to other MENA countries, the CNS cancers ASR(w) among Lebanese females (4 per 100,000 between 2005 and 2012) came fourth following Egypt (Damietta), Iran (Golestan), and Malta. However, female CNS cancers ASR(w) was among the lowest when compared to Non-MENA countries like Brazil and Norway (Table 4).

Full table

Discussion

This study describes the most recent trends in the incidence of CNS cancers in Lebanon. CNS cancers were the 11th most common cancers in Lebanon with a total of 2,309 cases over the studied period. Breast, Lung and colorectal cancers are the three most prevalent cancers in the Lebanese population (15-17). Males were generally more affected when compared to females, with a 34% increased risk. This is consistent with data published by other studies that found males to have higher risk of developing CNS cancers in general (18-20). However, male to female incidence rate ratios might vary depending on the histology of the CNS cancer, with some cancers like meningioma being two-fold higher in females (21-23). It has been suggested that gender differences are related to different genetic features, sex hormones, and working conditions, including higher exposure of men to pesticides and chemical agents (20,24).

CNS cancers had a general insignificant increasing trend for males (3.19%) and females (3.08%) over the studied period. CNS cancers ASR(w) among Lebanese males ranked 3rd when compared to other MENA countries. Egypt (Damietta) and Iran ranked first and second, respectively. For Lebanese females, CNS cancers ASR(w) ranked 4th following Egypt, Iran and Malta. Although CNS cancers represents 2% of adult cancers globally, however, these diseases are associated with significant burden because of its high fatality rate and its severe morbidity (25-27).

Several risk factors have been associated with increased risk of CNS cancers including ionizing radiation (26,27) and pesticide exposure (28-32). In Lebanon, several studies reported that the several wars and conflicts that occurred in the country caused high levels of depleted uranium (33,34). Moreover, CT scan radiations may contribute as well (35). In addition, the average GDP of Lebanon was approximately 33.2 million USD during the studied period (36), where agriculture contributed up to 80% in certain areas of the country and employed 30–40% of the total Lebanese population (37). An increase in agricultural activities and agricultural workers leads to higher pesticide usage, and eventually greater exposure among the population. The combination of these two factors may have contributed to higher incidence of CNS cancers when compared to other MENA countries. A meta-analysis including 14 articles found that high birth weight (>4,000 g) is associated with astrocytoma malignancies (38). This might have contributed to increased CNS cancers incidence in Lebanon, however, according to the available data on MoPH, only 2.9% of Lebanese newborn babies in 2015 are over-weight (39).

Several genetic factors for the onset of CNS cancers have been suggested in previous study. These factors include possessing variants of the Glutathione S-Transferase Gene (GSTT1) and MDM2 SNP309 Gene-Gene Interaction (40,41). A study by Salem et al. found the frequency of GSTT1 null Genotype among Lebanese population to be 37.6% (42). This may help explain the high incidence of CNS cancers in Lebanon. Moreover, TP53 gene with codon 72 polymorphism-dominant model and EGF polymorphism 61-G allele in Caucasians were associated with adult onset glioma (43-45). No significant data has been published concerning the expression of the above genes patterns in Lebanon. This prompts the need for detailed genetic testing for these genetic patterns among the Lebanese population, as well as improvement of the currently low research output, to better assess the risk of developing CNS cancers (46). Such genetic and epigenetic studies would further help us in targeted cancer therapies in Lebanon should these studies become available.

ASR(w) for CNS cancer in Lebanon for males and females was among the lowest when compared to non-MENA countries. The lower incidence of CNS cancers in Lebanon, and in MENA region in general, when compared to non-MENA countries is consistent with previous studies and can be due to several factors (47-49). In low- and middle-income countries, low CNS cancers incidence rate can be due to underdiagnosis, and therefore, underestimation rather than true lesser incidence. This is mainly because of less access to medical care and diagnostic services (50). Another factor might be the different standards for CNS cancers imaging and classification schemes among these regions. Variation in cancer reporting and registration systems might also play a role here as it has been found that cancer registries quality differs significantly by regions. For instance, only 1% of Africa’s population was covered by its cancer registries (49). This variation renders comparing different population-based registries more challenging and less accurate (48). Another important factor is related to the variation in inherited genetic risk by ancestry. This has been supported by studies in the US and UK that found lower incidence of CNS cancers among Asians living in the US and UK (51,52). Also, Ostrom et al. in their study of CNS cancers in US found gliomas histology type to be significantly less common in African Americans and Asian-Pacific Islanders than whites (47). Finally, other contributing causes to this regional variation might be exposure of different populations to different risk factors and unknown genetic or environmental risk factors.

Conclusions

Our study shows that Lebanon has one of the highest CNS cancers incidence in the MENA region. CNS cancers rate is increasing and age groups younger than 9 years and older than 30 years are much more influenced by the burden of these diseases than other age groups. Several risk factors might have contributed to this high incidence including ionizing radiation exposure, pesticide exposure, genetic predisposition and others. The available CNS cancers data in Lebanon should be improved to include histology and mortality rates to allow more detailed studies. Also, more genetic and epigenetic studies should be done in the country to better assess their effect in the development of CNS cancers in Lebanon.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cco.2020.04.02). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study does not require any institutional review board (IRB) approval as the data is deidentified and publicly available on the mentioned websites.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Khachfe HH, Refaat MM. Bibliometric analysis of Cardiovascular Disease Research Activity in the Arab World. Available online: http://icfjournal.org/index.php/icfj/article/view/554

- WHO. Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer

- Cancer.Net. Brain Tumor Guide. ASCO 2019. Available online: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/brain-tumor

- Perkins A, Liu G. Primary Brain Tumors in Adults: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2016;93:211-7. [PubMed]

- Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, et al. Molecular Principles of Metastasis: A Hallmark of Cancer Revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5:28. [Crossref]

- Collins VP. Brain tumours: classification and genes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75 Suppl 2:ii2-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herholz K, Langen KJ, Schiepers C, et al. Brain tumors. Semin Nucl Med 2012;42:356-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reilly KM. Brain tumor susceptibility: the role of genetic factors and uses of mouse models to unravel risk. Brain Pathol 2009;19:121-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- UN. World Statistics Pocketbook [Lebanon]. 2016. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publications/pocketbook/

- Fares MY, Fares J, Baydoun H, et al. Sport and exercise medicine research activity in the Arab world: a 15-year bibliometric analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2017;3:e000292. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MOPH. National Cancer Registry (NCR) of Lebanon. 2018. Available online: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/national-cancer-registry

- Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2017;XI. Available online: https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5-XI

- CI5PLUS: cancer incidence in five continents time trends [database on the Internet]2019. Available online: http://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5plus/Default.aspx. Accessed: 25/12/2019.

- Freddie Bray JF. Age standardization. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents XI. Available online: https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5-XI/Pages/Chapter7.aspx

- Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares MY, et al. Probing the Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Lebanon: an 11-Year Epidemiological Study. J Gastrointest Cancer 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salhab HA, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, et al. Epidemiological Study of Lung Cancer Incidence in Lebanon. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fares MY, Salhab HA, Khachfe HH, et al. Breast Cancer Epidemiology among Lebanese Women: An 11-Year Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoffman S, Propp JM, McCarthy BJ. Temporal trends in incidence of primary brain tumors in the United States, 1985-1999. Neuro Oncol 2006;8:27-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nomura E, Ioka A, Tsukuma H. Trends in the incidence of primary intracranial tumors in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2011;41:291-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edgren G, Liang L, Adami HO, et al. Enigmatic sex disparities in cancer incidence. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:187-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levy WJ Jr, Bay J, Dohn D. Spinal cord meningioma. J Neurosurg 1982;57:804-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamszus K. Meningioma pathology, genetics, and biology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2004;63:275-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bondy M, Ligon BL. Epidemiology and etiology of intracranial meningiomas: a review. J Neurooncol 1996;29:197-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKinley BP, Michalek AM, Fenstermaker RA, et al. The impact of age and sex on the incidence of glial tumors in New York state from 1976 to 1995. J Neurosurg 2000;93:932-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKinney PA. Brain tumours: incidence, survival, and aetiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75 Suppl 2:ii12-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chandana SR, Movva S, Arora M, et al. Primary brain tumors in adults. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:1423-30. [PubMed]

- Connelly JM, Malkin MG. Environmental risk factors for brain tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2007;7:208-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bassil KL, Vakil C, Sanborn M, et al. Cancer health effects of pesticides: systematic review. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:1704-11. [PubMed]

- Vinson F, Merhi M, Baldi I, et al. Exposure to pesticides and risk of childhood cancer: a meta-analysis of recent epidemiological studies. Occup Environ Med 2011;68:694-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Figà-Talamanca I, Mearelli I, Valente P, et al. Cancer mortality in a cohort of rural licensed pesticide users in the province of Rome. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:579-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Viel JF, Challier B, Pitard A, et al. Brain cancer mortality among French farmers: the vineyard pesticide hypothesis. Arch Environ Health 1998;53:65-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith-Rooker JL, Garrett A, Hodges LC, et al. Prevalence of glioblastoma multiforme subjects with prior herbicide exposure. J Neurosci Nurs 1992;24:260-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bešić L, Muhovic I, Mrkulic F, et al. Meta-analysis of depleted uranium levels in the Middle East region. J Environ Radioact 2018;192:67-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fares J, Khachfe HH, Fares MY, et al. Conflict Medicine in the Arab World. In: Laher I. editors. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer, 2020. doi.org/. [Crossref]

- Mathews JD, Forsythe AV, Brady Z, et al. Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ 2013;346:f2360. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salhab HA, Salameh P, Hajj H, et al. Stroke in the Arab World: A bibliometric analysis of research activity (2002-2016). eNeurologicalSci 2018;13:40-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Darwish R, Farajalla N, Masri R. The 2006 war and its inter-temporal economic impact on agriculture in Lebanon. Disasters 2009;33:629-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dahlhaus A, Prengel P, Spector L, et al. Birth weight and subsequent risk of childhood primary brain tumors: An updated meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vital Data Observatory Statistics [database on the Internet]. Ministry of Public Health. 2015. Accessed: 16/2/2019. Available online: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/vital-data-observatory-statistics

- Lai R, Crevier L, Thabane L. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferases and the risk of adult brain tumors: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1784-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wan Y, Wu W, Yin ZH, et al. MDM2 SNP309, gene-gene interaction, and tumor susceptibility: an updated meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2011;11:208. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salem AH, Yaqoob A, Ali M, et al. Genetic polymorphism of the glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genes in three distinct Arab populations. Dis Markers 2011;31:311-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi M, Huang R, Pei C, et al. TP53 codon 72 polymorphism and glioma risk: A meta-analysis. Oncol Lett 2012;3:599-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu W, Li Y, Wang X, et al. Association between EGF promoter polymorphisms and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Med Oncol 2010;27:1389-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang YM, Cao C, Liang K. Genetic polymorphism of epidermal growth factor 61A > G and cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol 2010;34:150-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fares MY, Salhab HA, Khachfe HH, et al. Sports Medicine in the Arab World. In: Laher I. editors. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer, 2020. doi.org/. [Crossref]

- Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008-2012. Neuro Oncol 2015;17 Suppl 4:iv1-iv62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miranda-Filho A, Pineros M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancers of the brain and CNS: global patterns and trends in incidence. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:270-80. [PubMed]

- Leece R, Xu J, Ostrom QT, et al. Global incidence of malignant brain and other central nervous system tumors by histology, 2003-2007. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:1553-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fares J, Salhab HA, Fares MY, et al. Academic Medicine and the Development of Future Leaders in Healthcare. In: Laher I. editors. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer, 2020. doi:. [Crossref]

- Chien LN, Gittleman H, Ostrom QT, et al. Comparative Brain and Central Nervous System Tumor Incidence and Survival between the United States and Taiwan Based on Population-Based Registry. Front Public Health 2016;4:151. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Research NCINaC. Cancer Incidence and Survival Major Ethnic Group, England 2002-2006. 2009. Available online: http://www.ncin.org.uk/view?rid=75