The United States’ national accreditation program for breast centers: a model for excellence in breast disease evaluation and management

Introduction

The American Cancer Society estimates that there will be 231,840 females diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and 60,290 with ductal carcinoma in situ in the year 2015 (1). At least 4 to 5 times of those numbers present annually with benign breast disease. This puts an enormous burden on the health care system, demanding evidence-based, streamlined evaluation and management of patients with breast disease.

In the 1970’s, Silverstein (2) recognized the disorganized and fragmented care being delivered to patients with breast cancer, and established the first multidisciplinary breast center. For the next three decades breast centers rapidly expanded across the country. But no one defined what a breast center really did. Accordingly, there was wide variation in their operational components.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS), established in 1913, has a long and rich history of setting standards of care and accrediting programs in cancer, trauma, bariatrics, and others currently under development. The Commission on Cancer (CoC), comprised of 55 national cancer-related, multidisciplinary organizations and societies, was founded in 1922 (3). It epitomizes the four pillars of quality improvement: (I) establish evidence-based standards; (II) assure that there is an appropriate facility infrastructure; (III) collect data; and (IV) verify compliance with the standards.

The CoC accredits over 1,500 cancer facilities in the United States, accounting for approximately 70% of cancer patients diagnosed annually. These facilities range from small community hospitals to National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers. Trained surveyors conduct an on-site triennial survey to verify compliance with standards and define deficiencies that must be corrected. Extensive data are collected for every cancer patient and reported to the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) annually. Established in 1989, the NCDB is the world’s largest clinical data base, containing information on 34,000,000 cancer patients (Personal communication, NCDB, American College of Surgeons).

Methods

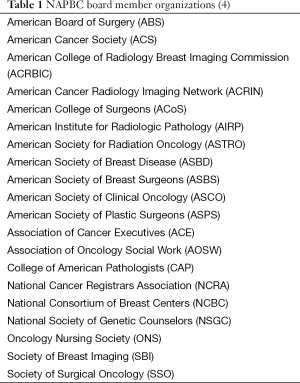

In 2006 the ACS convened a group of 15 national organizations to discuss a potential need for developing an accreditation program for breast centers. The concept was unanimously endorsed. The Board of Regents of the ACS approved developmental funds. A multidisciplinary board was appointed, now with representatives from 20 national organizations with an interest in breast cancer (Table 1). The name “National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers” (NAPBC) was adopted. The following mission statement was approved with slight modifications later: “The NAPBC is a consortium of national, professional organizations focused on breast health and dedicated to the improvement of quality outcomes of patients with diseases of the breast through evidence-based standards and patient and professional education.” Note that the NAPBC deals with both benign and malignant disease.

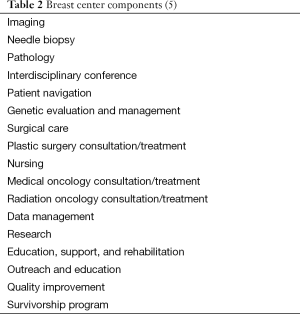

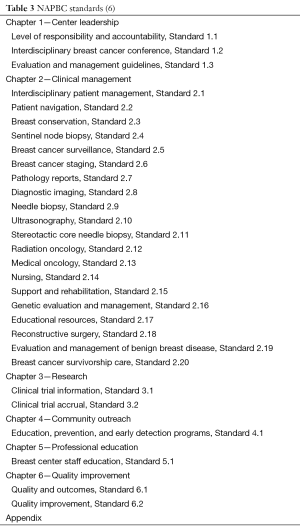

Tables 2,3 describe the NAPBC’s 17 components of breast care and the 27 standards, respectively. Initially the NAPBC was conceived as a tiered accreditation, based on breast cancer patient volume. Later a single accreditation was established by designating that the 17 components were either provided or referred. Most centers provide all components, but a few refer patients for some components, such as genetic counseling or MRI-guided breast biopsy.

In order to validate the standards, 18 pilot surveys were conducted in interested breast centers, ranging from small to large annual breast cancer patient accrual. This proved to be a valuable step, facilitating experience-based revision of the initial standards. In fact, this has become an ongoing process.

There is an important and increasingly utilized research component to the NAPBC. Most accredited breast centers are also accredited by the CoC. The breast file from the NCDB contains robust information and can be accessed by investigators from CoC-accredited centers. In 2015, 439 centers received a variety of files, the majority dealing with breast cancer. The NAPBC is engaged in expansion of the NCDB breast file and incorporation of the survey application record (SAR) from accredited breast centers to produce an even more robust research tool.

Results

After the 18 pilot surveys were completed, the first NAPBC applicant institution was surveyed and accredited in December, 2008. Since then, accreditation growth has been remarkable. As of December, 2015, 650 breast centers have been accredited and nearly 50 new programs are scheduled in the next few months. A survey of accredited centers (4) has defined the many benefits of becoming a NAPBC-Accredited Center:

- A model for organizing and managing a breast center to ensure multidisciplinary, integrated, and comprehensive breast care services;

- Internal and external assessment of breast center performance based on recognized standards to demonstrate a commitment to quality care;

- Recognition as having met performance measures for high-quality breast care established by national health care organizations;

- National recognition and public promotion;

- Participate in a National Breast Disease Data Base to report patterns of care and effect quality improvement;

- Access to breast center comparison benchmark reports containing national aggregate data and individual center data to assess patterns of care and outcomes relative to national norms.

There has been significant interest from countries outside the U.S. in the structure, process and outcome of the NAPBC. The challenges in meeting requests for foreign accreditation include staff time, revision of U.S. standards to meet developed, developing and under-developed countries’ circumstances, technical capacity for evaluation prior to the survey and time away from work for our physician surveyors. Security may be an issue in some settings. To date we have received interest from 32 breast centers from 17 countries.

Tawam Hospital, Ail-Ain, Abu Dhabi, affiliated with Johns Hopkins Medicine International, was the first international breast center to be accredited by the NAPBC. The North York Hospital Breast Center in Toronto is scheduled for survey in 2016. Other applicants expected for 2016 include Netcare Breast Unit of Excellence in Johannesburg, South Africa and the Breast Center at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal. Finally, there is a group of 8 centers in Colombia, Peru, and Argentina scheduled for follow up calls in early 2016.

Discussion

Breast cancer has a variable incidence around the world. In the U.S. the disease is common and public awareness and fears are high. These patients enter a highly complex medical environment, commonly in a high state of anxiety about their diagnosis, treatment and survivability.

The development of the NAPBC filled a previously unmet need to efficiently and compassionately navigate these patients through multiple tests and breast specialists’ consultations. In accredited breast centers, patients can expect state of the art evaluation, treatment and follow-up. Contrast this with the era prior to modern day evidence-based guidelines, accountability, and transparency, with increased public reporting and physician compensation tied to performance measures.

The NAPBC promotes the value proposition of improved quality at a lower cost. This cost reduction results from adherence to evidence-based guidelines, particularly in the evaluation phase, by eliminating or decreasing variation in the number and types of unnecessary diagnostic tests, such as advanced imaging for early stage disease.

There is an increasing focus on patient reported outcomes including shared patient decision-making with the provider, improved patient satisfaction, increased family engagement, sensitivity to, and intervention for, psychosocial distress, patient navigation and attention to the many components of quality of life.

With respect to the NAPBC standards referenced in Table 3, several highlights include:

- An applicant for the NAPBC must meet three critical standards to qualify for survey; designation of leadership responsibility and accountability, the formation of an interdisciplinary breast cancer conference, and interdisciplinary patient management (standard 1.1, 1.2, 2.1);

- A target rate of 50% for all eligible early stage breast cancer, stages 0, 1 and 2, are offered breast conserving surgery (BCS). This surveillance measure is designed to gather data on the frequency of BCS and is not a required percentage (standard 2.3);

- The College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines are required for all breast cancer pathology reports;

- Palpation or image-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) for cytology or core needle biopsy (CNB) are the initial diagnostic approaches, rather than open biopsy. This decreases the number of surgical procedures, especially if initial open biopsy fails to clear margins (standard 2.9);

- Genetic evaluation and management are crucial for identifying individuals at risk for familial or hereditary breast cancer syndromes (standard 2.16);

- All mastectomy patients are offered a preoperative referral to a plastic/reconstructive surgeon. Note that some patients will decline this offer (standard 2.18);

- Evaluation and management of benign breast disease follow nationally accepted guidelines. NAPBC includes common benign conditions, particularly atypical lesions (standard 2.19);

- A breast cancer survivorship care plan is provided to patients upon completion of treatment. The importance of recognizing and coordinating the transition from patient under treatment to survivor cannot be over emphasized;

In summary, the NAPBC in the U.S., and increasingly abroad, sets evidence-based standards designed to optimize the evaluation and management of patients with commonly encountered benign and malignant diseases of the breast. Triennial, on site visits by trained surveyors assures compliance and identifies deficiencies requiring correction within 12 months. The ultimate success of the program depends on the demonstration of improved outcomes in several dimensions relative to non-accredited facilities.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015.

- Silverstein MJ. The Van Nuys Breast Center: the first free-standing multidisciplinary breast center. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2000;9:159-75. [PubMed]

- Nahrwold DL, Kernahan PJ. The American College of Surgeons 1913–2012. Chicago (IL): American College of Surgeons; 2012.

- NAPBC Standards Manual 2014 Edition. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, 2014;6-7.

- NAPBC Standards Manual 2014 edition. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, 2014;15.

- NAPBC Standards Manual 2014 edition. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, 2014;4-5.